Nonsense Curves and Pyramids

Safety likes nothing more than curves and pyramids, nothing so exciting as parading out the Bradley Curve or Heinrich’s Pyramid to get the troops excited about failure and loss.

Safety likes nothing more than curves and pyramids, nothing so exciting as parading out the Bradley Curve or Heinrich’s Pyramid to get the troops excited about failure and loss.

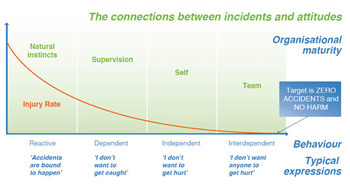

The Bradley Curve was created by DuPont in 1995 to try and benchmark notions of culture and performance in relationship to safety. Like all curves, it is a geometric attempt to plot an organisations journey in safety. The Bradley Curve assumes that high injury rates are due to people not taking responsibility. It is a simplistic understanding of causation and totally ignores many social psychological causes for mistakes. The Bradley Curve also demonizes natural instincts as if intuition, heuristics and unconscious choice is wrong. Natural instincts are associated with high accident and injury rates and, obviously injury rates are the measure of culture? The curve projects on to humans a behaviourist and individualistic anthropology that doesn’t match reality. The whole measure of determining a safe culture is based on an increase or decrease in injury rates.

The Bradley Curve is also premised on the ideology of zero. As one cruises down the curve in binary bliss, the absence of injury demonstrates ownership and responsibility. In the Bradley Curve safety is manufactured as a mechanistic process, luck is evil and the very denial of zero is determined as an attitude that incidents will happen. In most presentations of the Bradley Curve it is also assumed that the presentation of the curve will motivate people to care about safety. Through a process of observing curves and pyramids, somehow people will be motivated to create a safety culture.

If one looks up the Bradley Curve in Google images one can see the influence this curve has had on the way safety interprets culture and performance. The assumption of connection between injury rates and attitudes is assumed not demonstrated. Of course, if one gets to zero one is deemed ‘world class’, a remarkable achievement that can be just as easily achieved through hiding data and under reporting. What is even more remarkable is the lack of definition of harm and what qualifies as injury. I would have thought one was more world class for admitting that mental health was a form of workplace harm than denying it.

If one looks up the Bradley Curve in Google images one can see the influence this curve has had on the way safety interprets culture and performance. The assumption of connection between injury rates and attitudes is assumed not demonstrated. Of course, if one gets to zero one is deemed ‘world class’, a remarkable achievement that can be just as easily achieved through hiding data and under reporting. What is even more remarkable is the lack of definition of harm and what qualifies as injury. I would have thought one was more world class for admitting that mental health was a form of workplace harm than denying it.

One of the things that is convenient about curves and pyramids is that they are neat and tidy, giving a sense of order and control. What Taleb (2010 The Bed of Procrustes. p. x) calls ‘squeezing life and the world into crisp commoditized ideas, reductive categories, specific vocabularies and prepackaged narratives’. Rather than filling safety training with tidy formulas and pyramids of convenience we should be much more in tune with nature of randomness, resilience and risk. Current texts in WHS proudly parade pyramids, swiss cheese and curves as a source of intelligence about incident investigation, causation and understanding safety. I think Taleb is right in associating the commoditization of safety ideas with Procrustes, chopping off and stretching body parts as seen to ‘backward fit’ the mythology. Even to challenge the curve or pyramid evokes all kinds of defense from those with sunk cost in the game. Even their own statistics don’t match the curve or pyramid. Like finding meaning in the entrails of a goat, the curves and pyramids are defended like sacred objects in the religion of safety fundamentalism. My god, they are even sacralised with predictive value.

The pyramid is a much older creation than the curve but is nonetheless as fixed. Despite all the evidence to show Heinrich’s pyramid as the fictional manufacture of an insurance salesman in 1931, safety defends this myth more than a fundamentalist defends the Bible. There is no ratio to risk, this is why risk is about uncertainty. There is no mathematical construct for randomness, the ‘rain falls on the just and unjust’ the same as the dance of death visits without predictability. This is not to endorse fatalism but rather to say that the manufacture of control, the language of absolutes and the commoditization of risk offers no maturity for people in safety.

What I find most troubling about the fixation with curves, cheese and pyramids is the bizarre notion that these in some way inspire safety? Yet, so little is discussed in the safety world about inspiration, motivation and imagination. So whilst safety accepts the imagination of Bradley and Heinrich it can’t imagine that these are just dated constructs. It can’t imagine a safety without such misguided props and their misdirected focus. It can’t imagine what safety might look like without these superstitious trinkets, to ward off the evil of unpredictability and uncertainty.

There is a way ahead without these, a way that values people more than data, that values engagement more than counting and learning more than risk aversion. The way ahead involves letting myths go and un-learning constructs that commoditize. If you want to find out more about a better way to do risk and safety then check out the post graduate program at ACU or email at admin@humandymensions for more information.

Wilmar Rico says

Science is based materialistic methods, it means science need to understand the physics first (property of materials) then metaphysic (related to human beings) as per Aristotelian knowledge classification and basement of modern scientific methods.

Engineering and safety are based on above, so whatever is not measured and predictable by algorithms is immediate discarded.

In safety, specialists love curves, tables, formulas, etc. These methods keep safety specialists and managers feeling in their zone-of-comfort, following their bias.

Your approach in focusing response in instincts (automatic behavior) obey in what neuroscience studies explains regarding humans behavior is mostly (>95% of our daily acts) automatic or instinctive.

So, risks will happen and we’ll act 95% of time instinctively in normal life and of course under stress or risk around or inside us.

What ever is built by humans is affected by the human reliability. So there is not any machine, system, industry, free from human acts.

An example is the cheese models based on layer of protection that must be independent from each other. But each LoP is designed, constructed, maintained, modified, by humans. So, affected by humans reliability.

Human reliability will incorporate risks into the LoP and the process it self.

We could say that if we want to effectively increase the safety then increasing of human reliability by improving the human instinct is a safety target.

Rob, thanks for your great contribution in creating new paradigms!

Rob Long says

Thanks Wilmar. I find it so amusing that Safety loves to parade itself as ‘science’ and ‘professional’ when so much of what it speaks and symbolises is metaphysical and mythical.

Glad you appreciate my work, not many do. Especially those who attribute criticism and deconstruction as evil.

Wynand says

At least admitting to doing “Safety” due to financial reasons is more honest than most of the other motivations.

Admin says

I’ve been in quite a few inductions where they stated up front that it was a waste of time but had to cover themselves – little did they realise that they were simply condemning themselves

Rob Long says

Most inductions I have seen and been asked to assess are terrible. All have been full of boring safety mythology, excessive and none of it helpful. Greg Smith would tear it to shreds in court too. So much stuff spewed out in safety is simply not legally required nor defendable in court.

Jason says

Seems like a misunderstanding / semantics issue to me.

Of course no want wants ‘anyone else to get hurt’ and I can see how this curve might be offensive to people in a workplace that still has a reactive culture because it seems to indicate otherwise. But just by having management push the Bradly Curve almost automatically moves you into the dependent stage that the author seems to be complaining most industries do to pretend they are at near 0.

I worked at DuPont, and they were clear that this was not BS, but rather a legal issue, and that one was expected to even report paper-cuts as they could become infected and be a liability for the company. This admission kept them from the pitfalls of moral-less companies trying to pretend they have morals and doing ‘safety because it’s the right thing to do’ and into the domain that companies actually care about ‘safety because it’s a finical liability’ and thus was a metric they wanted a true handle on / not something to be buried.

Rob Long says

Meanwhile DuPont knowingly hides the toxification of water and harms tens of thousands of people (https://safetyrisk.net/dark-waters-the-true-story-of-dupont-and-zero/). Even so, the opening comment about semantics is a strange one, issues with semantics are no small issue indeed, being naive about semantics starts wars. So not sure if this opening is somehow trying to dismiss the value of semantics, a sub-set of semiotics/linguistics. Obviously DuPont didn’t think what they said needed to match what they practiced and certainly showed they have no moral or ethical compass.

As for the semiotics of the curve, it has no substance or evidence to support it. It’s just a model and a flawed one at that, all precipitated on the delusions of human perfectionism and infallibility. It is clear now however based on the evidence that DuPont never gave a shit about zero.

Admin says

So Dupont’s priority is the safety of the company?

Rob Long says

Rob, I would be most interested in what you mean by ‘works’?

Rob G says

I cannot agree with the premise here. Having been in engineering for 25 years, the last 15 years in engineering management and having been investigated for a serious harm incident for one of my staff, I can faithfully say that the Bradley Curve does work. Attitude does matter and merely palming things off for psychology, culture and a bunch of other things demonstrates one is not at the end point yet – and that’s OK. Eventually one realises these things need to change too. It takes real humility to accept this and move to the next point on the journey. The company I worked at previously for seven years had to have a death to start the change, but we did get there in the end.

Chris Jones says

Hats off to you, fella! I am a safety professional with 25 years standing with a degree in cognitive ergonomics. Very early in my career I became acquainted with the DuPont ‘way’ of doing things and have found it to be fatuous bullshit. End of…

ab says

In the chemical industry its all about bow ties, LOPA studies etc. Its just a way to mask poor process controls & ‘appear’ to be doing something about it. Yes risk assessment is good, but only if conducted by a highly qualified & technically competent group of professionals. Good design, process controls, equipment & procedures will lead to less accidents, but many risk assessments I’ve seen merely justify the reason for making no improvements (cost cutting).

Admin says

Dupont must be doing some soul searching after some of their recent incidents – world class safety?

Pasquale Bambaci says

Being in the mining sector for 8 years, previously owning small enterprises i have come to the understanding for all to achieve a better safety culture and increase in productivity and profitability all have to change in the way we approach our work life , caring for our colleagues creating a culture that has respect for one life a happy workforce is more productive and achieves results in all aspects

Admin says

Yes – that methodology certainly works when we are with family or friends – people we truly care about! No silly curves and pyramids required there……