Originally posted on June 20, 2015 @ 8:48 PM

Safety and The Sunk Cost Fallacy

In a recent debate on LinkedIn the discussion turned to the effectiveness or otherwise of concepts such as zero harm, BBS and other safety fads. Someone asked the question: “if so many people realise that this stuff doesn’t work or is even harmful then why do we persist with it?”. In the context of an individual or group then I think the main reason is Cognitive Dissonance (rationalising our thoughts to feel more comfortable about something that may be against our values or that we disagree with). However, the question was more aimed at a government or organisational level and my short response to the question was “SUNK COST”. It seems, from the research I have done, that sunk cost is not a term often associated with safety, economic risk definitely, but not safety.

In a recent debate on LinkedIn the discussion turned to the effectiveness or otherwise of concepts such as zero harm, BBS and other safety fads. Someone asked the question: “if so many people realise that this stuff doesn’t work or is even harmful then why do we persist with it?”. In the context of an individual or group then I think the main reason is Cognitive Dissonance (rationalising our thoughts to feel more comfortable about something that may be against our values or that we disagree with). However, the question was more aimed at a government or organisational level and my short response to the question was “SUNK COST”. It seems, from the research I have done, that sunk cost is not a term often associated with safety, economic risk definitely, but not safety.

This explains then why a few people asked me, offline, why I would give that answer. To me it made perfect sense but I guess to others it has a different meaning. I remember first learning about sunk cost during economics classes at school and quickly sent it to the bottom memory draw until it came up again when I started learning about social psychology of risk and safety. To me “sunk cost” is the unwillingness to give up something, even though you know it won’t work or there is something better, because you have already “sunk” so much irretrievable time, money, emotion, pride, talk etc etc into it. It’s known as the sunk cost “fallacy” because these decisions seem to be made based on illogical reasoning – Dr Spock would not make such irrational decisions but humans do!

The more I learn about sunk cost and the hundreds of other biases, the more I realise how important they are in understanding why people make the decisions they do about risk and safety. If more safety people were aware of these concepts then we could start to move away from the orthodox, mechanistic management of risk and the misconception that risk is objective – sunk cost fallacy proves that it SO ISN’T! . Have a read of some of the stuff below and tell me if you think my answer to the original question was valid – I’m thinking now that not knowing about the importance of sunk cost, in how humans make decisions, may be the first hurdle?

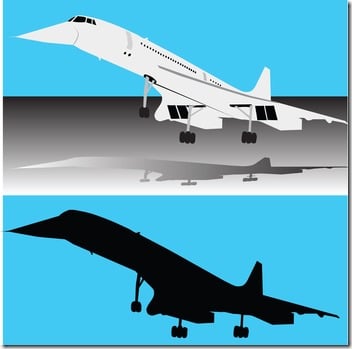

The sunk cost fallacy is sometimes known as the “Concorde Fallacy” – referring to the development of the Concorde by Aérospatiale and the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) under an Anglo-French treaty. Early in its development the British and French governments knew that there was no longer a sound economic reason to have such an aircraft, the project should never have been started and it would likely be a commercial disaster. But both governments continued to fund the project, costs ran way over, and it was almost cancelled, but psychological burdens outweighed rational judgments and political and then legal issues ultimately made it impossible for either party to pull out.

Some interesting points from The Critical Uncertainty Blog:

- Plan continuation bias (another name for sunk cost) is a recognised and subtle cognitive bias that tends to force the continuation of an existing plan or course of action even in the face of changing conditions. In the field of aerospace it has been recognised as a significant causal factor in accidents, with a 2004 NASA study finding that in 9 out of the 19 accidents studied aircrew exhibited this behavioural bias. One explanation of this behaviour may be a version of the well known ‘sunk cost‘ economic heuristic.

- Economists argue that sunk costs (what we have spent in the past) should never be used when making rational decisions about future events. So for example if I’ve bought a ticket to the ballet, I should not decide to go on the basis that I have spent money on the ticket. Instead the decision should be based on what my current circumstances are, e.g. ‘I’ve just learned that my favourite ballerina is not dancing, therefore I won’t go’, rather than ‘I have spent all this money and I don’t want to waste it…’.

- Of course as the example above illustrates, and behavioural economists point out, this is notexactly how human beings really behave. In practice people tend to apply the so called sunk cost heuristic to a greater or lesser degree. In summary the heuristic reflects that human beings are averse to loss so we tend to bias our decision in a way that demonstrates our reluctance to write of any sunk cost as a loss.

- There are also two predominant factors that characterise the heuristic. The first is an over optimistic estimate of probability of success, possibly to reduce cognitive dissonance having made a decision. The second is that of personal responsibility, when you are personally accountable it is difficult to admit you were wrong.

From Dr Rob Long in “Keep Discovering”:

Talking about an impressive European company he recently worked with and their trademarked “Nimblicity”: In this word they acknowledge the reality of fast and frugal decision making (heuristics), so well articulated by Gigerenzer (author of Risk Savvy and many other texts). Organisations that get bogged down in their own sunk cost will rarely be creative or innovative.

Rob Sams raise the concept in his blog post : Risk is about people, not just objects

As David McRaney explains so well on his website; “The Misconception: You make rational decisions based on the future value of objects, investments and experiences. The Truth: Your decisions are tainted by the emotional investments you accumulate, and the more you invest in something the harder it becomes to abandon it.” Do you have ‘sunk cost’ as one of the items on your risk assessment checklist?

David McRaney’s Website is “You are not so smart” and his post “The Sunk Cost Fallacy” is a great read. Some points he makes:

- Whenever possible, you try to avoid losses of any kind, and when comparing losses to gains you don’t treat them equally. The results of his (Kahneman’s) experiments and the results of many others who’ve replicated and expanded on them have teased out a inborn loss aversion ratio. When offered a chance to accept or reject a gamble, most people refuse to make take a bet unless the possible payoff is around double the potential loss.

- Behavioral economist Dan Ariely adds a fascinating twist to loss aversion in his book, Predictably Irrational. He writes that when factoring the costs of any exchange, you tend to focus more on what you may lose in the bargain than on what you stand to gain. The “pain of paying,” as he puts it, arises whenever you must give up anything you own. The precise amount doesn’t matter at first. You’ll feel the pain no matter what price you must pay, and it will influence your decisions and behaviors.

- When you lose something permanently, it hurts. The drive to mitigate this negative emotion leads to strange behaviors. Have you ever gone to see a movie only to realize within 15 minutes or so you are watching one of the worst films ever made, but you sat through it anyway? You didn’t want to waste the money, so you slid back in your chair and suffered.

- You know a loss lingers and grows in your mind, becoming larger in your history than it was when you first felt it. Whenever this clinging to the past becomes a factor in making decisions about your future, you run the risk of being derailed by the sunk cost fallacy.

- Sunk costs drive wars, push up prices in auctions and keep failed political policies alive. The fallacy makes you finish the meal when you are already full. It fills your home with things you no longer want or use. Every garage sale is a funeral for someone’s sunk costs.

- It is a noble and exclusively human proclivity, the desire to persevere, the will to stay the course – studies show lower animals and small children do not commit this fallacy. Wasps and worms, rats and raccoons, toddlers and tikes, they do not care how much they’ve invested or how much goes to waste. They can only see immediate losses and gains. As an adult human being, you have the gift of reflection and regret. You can predict a future place where you must admit your efforts were in vain, your losses permanent, and when you accept the truth it is going to hurt.

Do you have any thoughts? Please share them below