Culture and Subculture, Which is Safety?

The SIA BoK chapter on Organisational Culture came out this week. I read with interest that there was no intentional discussion of subcultures in the paper. Of course with so much sunk cost the club will surround the wagons and defend, that’s what it does. Inclusivity is not what it does. The idea of subcultures is not new, in the tradition of Critical and Cultural Studies a subculture is a group of people that differentiates itself from the larger culture to which it belongs. If you really want to get a sense of subculture then perhaps watch a few episodes of Bogan Hunters or Housos, Upper Middle Bogan or Pizza. You get some sense of the nature of the subculture by Joining the facebook site . It would have been valuable to see a discussion of subculture and subcultural analysis in the SIA BoK paper, but it is not there.

The SIA BoK chapter on Organisational Culture came out this week. I read with interest that there was no intentional discussion of subcultures in the paper. Of course with so much sunk cost the club will surround the wagons and defend, that’s what it does. Inclusivity is not what it does. The idea of subcultures is not new, in the tradition of Critical and Cultural Studies a subculture is a group of people that differentiates itself from the larger culture to which it belongs. If you really want to get a sense of subculture then perhaps watch a few episodes of Bogan Hunters or Housos, Upper Middle Bogan or Pizza. You get some sense of the nature of the subculture by Joining the facebook site . It would have been valuable to see a discussion of subculture and subcultural analysis in the SIA BoK paper, but it is not there.

Hebdige (1979) first wrote on subculture in Subculture, the Meaning of Style and argued that a subculture is a ‘subversion of normalcy’. One thing that the SIA BoK paper seems to endorse is that the notion of ‘safety culture’ is erroneous or as Dekker puts it ‘ontological alchemy’. The SIA BoK certainly canvasses the many problems with definition and one of the most consistent factors in the safety culture literature is that it is rarely defined and mostly assumed. It seems that training and experience in safety makes one an expert on culture. In the last half dozen or so books I have bought on safety culture and leadership, none defined culture and most defined management as leadership. Most spoke of culture as some objectified object that could be measured and quantified.

The most common definition of culture that seems to float about is that safety (culture) is about behaviours. This understanding seems to be perpetuated by the Behavioral Based Safety (BBS) tradition and DuPont. The SIA BoK describes safety culture as a ‘definitional dilemma’ and certainly there is an extensive history of definition of safety as error and behavior founded in Reason (1997). This focus seems to help perpetuate the myth that injury is a measure of safety culture. The fixation with injury measurement as a measure of safety culture is now so entrenched it is assumed to be self evidently true.

Perhaps one of the best statements in the SIA BoK paper is: ‘After close to 30 years, the body of safety culture literature is plagued by unresolved debates, and definitional and modeling issues. As a result, safety culture is a confusing and ambiguous concept, and there is little evidence of a direct relationship between it and safety performance’ (p.17). Ah, so it’s a ‘wicked problem’, perhaps unresolvable. Once we know that risk is a ‘wicked problem’ then we can escape from the nonsense confines of systems and process, engineering and ‘the science’ of safety. Similarly, if humans are just a part of a system or part of a process as the ‘human factors’ tradition asserts then safety will continue the illusion that everything can be named and controlled.

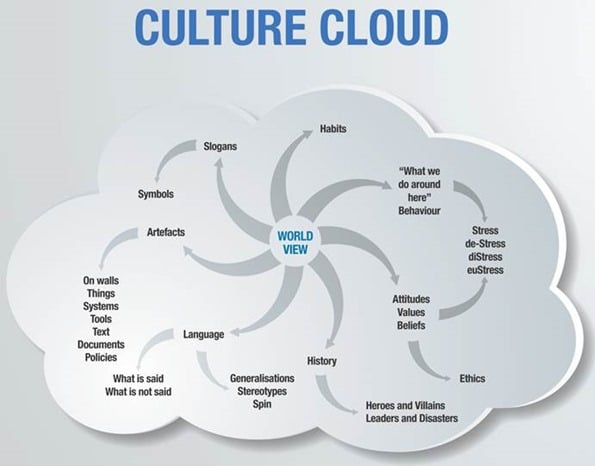

When I think and discuss culture I tend to use the metaphor of a cloud (or a range of other metaphors and symbols that best suit the context). Like all metaphors and semiotics the cloud comes with its own set of biases and understandings. However, if safety is looking for some objective ‘scientific’ and ‘quantifiable’ notion of culture, there isn’t one at least the SIA BoK makes that clear. I like the metaphor of the cloud because it gets away from the text heavy and table-focused thinking of academia. It is interesting in the SIA BoK paper that there are no images, as if semiotics itself is not a critical part of cultural understanding. Actually, I saw no discussion of semiotics at all in the SIA BoK paper, another critical omission.

I like the cloud metaphor because it swirls around with the wind, we can see it but not touch it. This gives value to the nature of turbulence and the shifting nature of work, organisations and enactment. The more we understand safety in such a context the less we are likely to be seduced by the ideology of zero and pseudo-science. Whilst we can scientifically explain clouds this is nothing like the aesthetics of seeing images in clouds, dreaming of clouds in poetry, giving clouds meaning in art and attributing feelings to clouds. Just think of Wordsworth:

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

I recently discussed other ways of seeing safety, through sound, colour, art and history.

https://safetyrisk.net/the-sound-of-safety/

https://safetyrisk.net/the-colour-of-safety/

https://safetyrisk.net/safety-is-an-art/

https://safetyrisk.net/history-and-hindsight-in-safety/

I think safety might gain a much better perspective on safety if it didn’t come to understanding through its own narrow discipline. Safety tends to think that the best way to come at safety is through law, engineering, regulation and science, just look at the structure of SIA conferences. Safety would gain much more by engaging with other disciplines.

Weick talks about ‘mutating metaphors’ as a means to understanding human organizing. Perhaps the best way to tackle the topic of culture and safety is to shift away from the scientific to the aesthetic. I think the cloud metaphor is far a more helpful metaphor for safety than the militaristic metaphors used to try and understand how we organize safety. Strange how some use a metaphor for the machinery of killing to provide a model of saving life.

Returning to the SIA BoK, it is interesting that critical elements of culture and subculture are either not discussed or emphasized in the SIA BoK paper. The paper tends to takes a systems-focused and process-focused approach. Interestingly the table on page 24 ‘Characteristics of an organization that focuses on safety’ there is no mention of semiotics, symbolism, history, social psychology, language and discourse. Not surprising given that the SIA endorses a mechanistic approach to safety just as it is not surprising that it endorses (through editorial practice), a zero harm ideology. It will be a surprising day when the SIA countenances a broader agenda and framework for engagement with the sector.

I can’t wait for the next instalment in the SIA BoK (December) for the release of Risk and Decision Making. I wonder what else the SIA BoK will omit from its body of knowledge?

Do you have any thoughts? Please share them below