Another brilliant essay by one of my fellow Students undertaking Graduate Certificate in The Psychology of Risk at ACU – published with permission

The key to leadership is motivation. What motivates people to become followers?

by Frank Kraemer from www.safebound.com.au

To generate sustainable motivation leadership needs to establish strategies and goals that suit follower’s self-regulatory orientations. In addition the use of framing methods to optimise goal pursuit should be considered as well as the conditional alignment of leadership styles in accordance with regulatory modes of followers. Ignoring the complexity of following-leading dynamics may cause followers to pursue goals other than those of their leaders.

To generate sustainable motivation leadership needs to establish strategies and goals that suit follower’s self-regulatory orientations. In addition the use of framing methods to optimise goal pursuit should be considered as well as the conditional alignment of leadership styles in accordance with regulatory modes of followers. Ignoring the complexity of following-leading dynamics may cause followers to pursue goals other than those of their leaders.

This essay will examine the theories of regulatory focus (Higgins, 1997), regulatory fit (Higgins, 2000) and regulatory mode (Higgins, Kruglanski, & Pierro, 2003; Kruglanski et al. 2000) in relation to following, leading and motivation.

First I will outline conventional assumptions about intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, early motivation theories and provide Higgins’ (2011, p. 42) definition of motivation. I will then explain the meaning of value, truth and control effectiveness as vital components of motivation. Next I will debate regulatory focus theory to explain how follower’s prevention and promotion focus orientations determine their preferred way of goal pursuit. Subsequently I will argue that regular fit assists with sustaining motivation and describe how framing strategies induce regular fit. I will conclude by examining the impact of regulatory mode dimensions ‘assessment’ and through different leadership styles.

People enter activities because they are extrinsically, intrinsically motivated, or both (Higgins, 2011, p. 229). Whilst intrinsic motivation had many meanings and definitions over time Deci and Ryan (2013, p. 43) define intrinsic motivation as:

The innate, natural propensity to engage one’s interest and exercise one’s capacities, and in so doing, to seek and conquer optimal challenges.

Extrinsic motivation means doing something in order to receive a reward or avoid punishment. Higgins (2011, p. 60) suggests that the common assumption that extrinsic motivators undermine effectiveness don’t recognise the fact that they can offer rewards triggering intrinsic motivation. Early theories about motivation (Watson, 1913; Freud, 1920/1950; Skinner, 1938 cited in Cornwell, Franks, Higgins, 2014 p. 1) were based on the belief that humans are generally motivated for reasons of approaching pleasure and avoiding pain. Some of these theories describe motivation as a form of energy or drive being present in humans which can be directed towards goals. Theorists have accepted in the past that such energy would be created through provision of external incentives or biological needs i.e. the wish to survive (Higgins, 2011, p.20). The so called hedonic principle ancient Greek anatomists who assumed that the only individual or social good is happiness (Seward, 1939). However modern research has established that the hedonic principle does not explain all human behaviours when it comes to motivation. In this regard Riggio, Chaleff, Lipman-Blumen (2008, p. 337) comment:

Leaders should link motivation and reward to followers’ identities, activating the appropriate self rather than directly stressing specific goals. Such self-relevant linkages will be more powerful motivators because they engage a number of affective, cognitive, and behavioural processes that are not triggered by externally imposed goals.

Higgins (2011, p. X) states that research discovered that:

The value of something does not depend on its hedonic properties alone.

Instead of asking ‘what motivates followers’ Higgins (2011, p. 14) asked:

What is it that people want?

As a summary of a large body of research undertaken by him he comes to the conclusion:

Directing choices in order to be effective.

Higgins (2011, p. 15) adds that pleasure and pain (reward and punishment) typically function as feedback signals of success. As indicated in the quotes above people don’t just follow leadership for reasons of pleasure and pain but have rather more complex motives that will influence following-leading dynamics.

To provide a basis for motivation that is aligned with leadership’s goals three interdependent motivational dimensions of followers must be met: truth, value and control effectiveness. ‘Truth effectiveness’ means followers being successful in knowing what is real. Higgins (2011, p. 166) notes:

Trying to find the truth is not in itself beneficial. What matters is feeling that one has been successful at finding the truth (i.e., experiencing truth effectiveness).

‘Value effectiveness’ means followers being successful in achieving the outcomes they want. ‘Control effectiveness’ is accomplished best when followers perceive that they are able to influence or guide what happens, for example resisting temptations during goal pursuit, managing procedures, competencies or resources. How truth, value and control effectiveness work together is essential for motivation. In various combination they create commitment, strengthen engagement, help us to believe that we ‘go in the right direction’ and provide an impression of ‘feeling right’ by doing so (Higgins, 2011, p. 299). Whilst the motivational dimensions listed above provide a foundation for motivation they are not sufficient on their own. Important for the achievement of anything are goals and strategies to accomplish them.

The next paragraph will discuss the two independent self-regulatory orientations in humans and their role in goal pursuit strategies.

Higgins’ (1997) Regulatory Focus Theory is based on the fact that people are motivated when they have a desire to reach an end-state or goal. The theory explains that people follow goals based on their individual goal orientation which is either eagerness (promotion focus) or vigilance (prevention focus). Promotion focus in people relates to emphasis on accomplishment and advancements whilst pursuing goals. Prevention focussed individuals are orientated in terms of safety and responsibilities when following their goals. Both states may coexist whilst either one or the other is dominant in people. Such dominant state or focus is learned through interactions with people who are influential such as parents, friends or colleagues (Higgins, 1979 p. 1282). Regulatory focus orientation in people can be measured with the aid of questionnaires (Higgins et al., 2001 p. 8). However motivation is not automatically sustained and people may develop their own motives over time drifting towards other goals. To maintain motivation people’s regulatory focus orientation must match the strategic means in which a goal is pursued. Higgins (2000) called this phenomenon ‘regulatory fit’ theory. Higgins (2011, p. 10) explains:

When there is a fit between individuals’ prior orientation toward an activity and the manner of carrying out the activity, engagement in the activity is strengthened.

Whilst regulatory focus orientation is chronic in people momentary regulatory focus can be primed or induced (Idson, Lieberman, Higgins, 2004, p. 927). This means that the preference of a person to pursue a goal eagerly or vigilantly, can be influenced and regular fit can be created. The significance of this is that leaders can manipulate people to a degree to be more motivated to follow their course. Cesario, Higgins, Scholer (2008, p. 448) outline:

By priming regulatory focus, Lee and Aaker [2004] demonstrated that one does not need to know the idiosyncratic characteristics of recipients. Given that both promotion focus and prevention focus can be primed in all people, it is possible to begin a persuasive appeal by priming one or the other focus and then delivering a message framed in a way that fits.

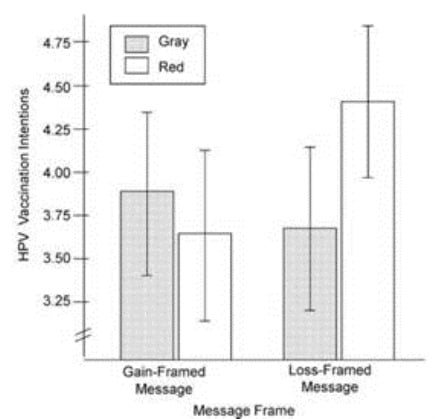

Framing and priming are techniques that can be used to positively influence follower’s perception of value, truth and control effectiveness during goal pursuit, hence to create regulatory fit. As briefly mentioned above regulatory fit influences in the following ways: making message recipients ‘feel right’ whilst the message is being received; increasing a recipients’ strength of engagement with the message, and influencing the chance of elaboration (Cesario, Higgins, Scholer, 2008, p. 444). As an example for the power of message framing Idson, L. C., Liberman, N., Higgins, E. T. (2004, p. 928) describe a study in which a book could be purchased by either paying cash or pay by credit card instead of using cash. By means of message framing the price difference was framed in one situation as ‘discount’ for using cash and in the second as ‘penalty’ when using the credit card. As a result people with promotion orientation experienced ‘gaining’ a discount (by paying cash) as positive and people in prevention focus felt that avoiding a penalty by paying cash was an advantage. Participants in both of these groups reported a ‘feel good’ factor. A study by Gerend, M. A. and Sias, T. (2009) highlighted that framing does not necessarily depend on verbal or written messages alone but can be reinforced through priming techniques using particular colours. In their study young men have been asked to read messages regarding vaccinations. The messages presented were either gain or loss framed and surrounded by grey or red colour. The study found that those that were exposed to the loss-framed message and the colour red had the greatest intentions to get vaccinated.

Figure 1: Framing through colours – Gerend, M. A. and Sias, T. 2009 study results.

the contrary can be achieved when task framing is not well understood. Higgins (2011, p. 22) refers to a study that demonstrates how adding fun to a particular learning activity resulted in non-fit with participating individuals when the task was perceived as a serious learning activity and therefore didn’t match participants regulatory focus. This and similar studies have highlighted that motivation can be decreased when incentive schemes are not well designed. Non-fit can reduce engagement strength (Higgins 2011, p. 247).

In addition to encouraging followers through means of message framing leaders can influence job satisfaction and resulting motivation by adjusting their leadership style. The way leaders exert power will influence the follower’s motivation. Evidence from research by Higgins, Kruglanski and Pierro (2007) shows that the two fundamental components of regulatory mode (Higgins, Kruglanski, and Pierro, 2003; Kruglanski et al. 2000) ‘assessment’ and ‘locomotion’, play an important part in following-leading dynamics. Both components are part of each regulatory focus (prevention and promotion). They are also part of people’s self-regulatory activities and defined by Kruglanski, A. W, et al., 2000, p. 794) as:

[Assessment] – judging the quality of something by considering both its merits and demerits in comparison with an alternative.

[Locomotion] – initiating movement away from some current state, sustaining smooth movement in goal pursuit.

The relation above dimensions have with leadership styles and therefore with the exertion of power lies in the understanding (Higgins, Kruglanski, Pierro, 2007, p. 137), that followers tend to prefer certain leadership styles depending on their personality dimension (assessment or locomotion). French and Raven (cited in Higgins, Kruglanski and Pierro, 2007 p. 137) have identified five different types of social power: coercive power (punishment), legitimate power (normatively accepted right to exert influence), expert power (recognised knowledge), referent power (respect/obligation) and reward power (pleasure, money). Bui, Raven and Schwarzwald (cited in Higgins, Kruglanski and Pierro, 2007 p. 137) have divided these five powers into two categories to which they refer to as ‘forceful’ as in strong/autocratic and ‘advisory’ as in soft/democratic. Kruglanski, Pierro and Higgins (2007, p. 143) have matched both categories with regulatory mode orientations and found that those with locomotion focus prefer ‘forceful’ leaders and those with assessment focus prefer ‘advisory’ leadership styles. Job satisfaction increases when regulatory mode matches the preferred leadership style (Higgins, Kruglanski, Pierro, modes presents itself as a strategy for successfully attracting followers.

Research over the last decades has provided certainty that the simplicity of the hedonic principal is insufficient in its goal of achieving enduring motivation. Socially influencing people to willingly pursue goals requires them to experience truth, value and control. When these motivational dimensions fit their regulatory orientation and leadership styles suit their regulatory mode they are likely to become truly motivated followers.

Bibliography

Cesario, J., Higgins, E. T. and Scholer, A. A., 2008. Regulatory Fit and Persuasion: Basic Principles and Remaining Questions. Social and Personality Psychology Compass.

Cornwell J. F. M., Franks, B., Higgins, E. T., 2014. Truth, control, and value motivations: the “what,” “how,” and “why” of approach and avoidance. Department of Psychology, Columbia University.

Deci, E., Ryan, R. M., 2013. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in

Human Behavior. Springer Science & Business Media.

Gerend, M. A., Sias, T., 2009. Message framing and color priming: How subtle threat cues affect persuasion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

Higgins, E. T., Friedman, R. S., Harlow, R. E., Idson, L. C., Ayduk, O. N. and Taylor, A., 2001. Achievement orientations from subjective histories of success: Promotion pride versus prevention pride.. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol.

Higgins, E. T., Kruglanski, A. W., & Pierro A., 2003. Regulatory mode: Locomotion and assessment as distinct orientations. Advances in experimental social psychology.

Higgins, E. T., 1997. Beyond Pleasure and Pain. American Psychologist.

Higgins, E. T., 2000. Making a good decision: Value from fit. American

Psychologist.

Higgins, E. T., 2005. Value from regulatory fit. Current Directions in

Psychological Science.

Higgins, E. T., 2011. Beyond Pleasure and Pain: How Motivation Works. s.l.: Oxford University Press.

Idson, L. C., Liberman, N., & Higgins, E. T., 2004. Imagining how you’d feel: The role of motivational experiences from regulatory fit.. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

Kruglanski A. W., Pierro, A., Higgins E. T., 2007. Regulatory Mode and Preferred Leadership Styles: How Fit Increases Job Satisfaction. Basic and Applied Social Psychology.

Kruglanski, A W; Thompson, E P; Higgins, E T; Atash, M N; Pierro, A ; Shah, J Y ; Spiegel, S, 2000. To do the right thing! or to just do it!: Locomotion and assessment as distinct self-regulatory imperatives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Lee, A. Y., & Aaker, J. L., 2004. The influence of regulatory fit on processing fluency and persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Riggio, R. E., Chaleff, I.,Lipman-Blumen, J, 2008. The Art of Followership: How Great Followers Create Great Leaders and Organizations. s.l.: John Wiley & Sons.

Seward, G. H., 1939, Dialectic in the psychology of motivation. Psychological Review.

Do you have any thoughts? Please share them below