That’s Not a Knife, That’s a Knife

Dr Rob Long

Sometimes when I get a chance to catch up with my brother Graham I feel like the hoodlum on the streets of New York in Crocodile Dundee. Not that we compete as brothers but when it comes to risk I have a lot to learn from Graham. It’s not until you walk through the doors of The Wayside Chapel that you realize you don’t know much about risk.

Sometimes when I get a chance to catch up with my brother Graham I feel like the hoodlum on the streets of New York in Crocodile Dundee. Not that we compete as brothers but when it comes to risk I have a lot to learn from Graham. It’s not until you walk through the doors of The Wayside Chapel that you realize you don’t know much about risk.

Graham is the Pastor and CEO of the Wayside Chapel Kings Cross in Sydney (http://www.thewaysidechapel.com/). When it comes to wisdom in embracing risk I realize that what is done at Wayside is miraculous. Kings Cross is the place that amplifies the best and worst of what it is to be human. At the Wayside, there is no hiding of abuse and homelessness behind the doors of a middle class mortgage, there is no denial of addiction to substances hidden behind the doors of pristine offices and site sheds, there is no hiding of harm behind delusional slogans as if people are perfect and, no hiding of statistics in ‘spin’ or the fact that there by the grace of god, go I.

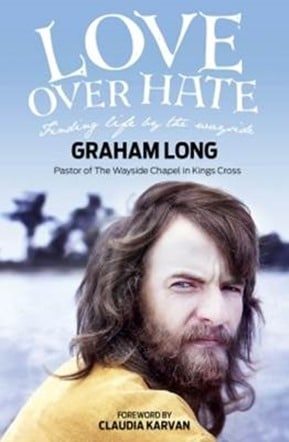

Graham has recently released his second book ‘Love Over Hate, Finding Life by the Wayside’. If you would like to read Graham’s amazing life story and philosophy you can purchase his book here

One message in Love Over Hate and The Wayside Chapel is about embracing the realities of risk and about learning in the face of delusions of control. Some excerpts from the book give an idea of what works in dealing with some of life’s greatest risks:

‘At The Wayside, we tell people they are not ‘problems’ to be solved but rather ‘people’ to be met. We know we have had a good day if someone walks out of our front door feeling ‘met’ rather than ‘worked on’. Mostly, people anticipate they will be treated as problems rather than as persons – indeed, most seem to insist on it, as this has been their experience in the past – but to flourish as a person, the essential ingredient is to know that you belong with others’ (p. 14).

‘Nobody wants to be given the gift of frailty, but it can be a fun gift to give when it opens the door to connection and community, and the possibility of security. Perfectionism, on the other hand, shuts down any possibility of connection and community. In all its many forms perfectionism is just another kind of addiction and, like all addictions, much is promised but little is delivered’ (p. 66).

‘A feather is the tool with which I do battle. The feather is at once powerful and pathetic. Some acts of power are crude and brutal and some are smooth, impressive and technically brilliant acts of non-redemption. The power of the feather comes in the act of naming something for what it truly is. The feather will never kill anyone, but it can make us laugh. It can detect when the promises made in an election campaign carry into our culture the sweet smell of a brothel. The feather can irritate or soothe or tickle. Approaching a battle with a feather needs understanding and gentleness, a certain steadfast spirit and an eye for detecting bullshit or political correctness gone wrong’ (p. 81).

There are some powerful messages in Graham’s story and The Wayside Chapel for those in the risk and safety industry. Whilst the zero harm delusion rages in its cocoon of anti-learning culture, Wayside knows that the best way to help a fallible human-as-addict is by a drug injecting room. In a drug injecting room harm is embraced and a little harm is advocated for the prospect of future wellness. In the Wayside the denial of harm is nonsense. In the medical profession there is no denial of harm because even in the act of vaccination we cause pain and inject some harm so the body can produce anti-bodies. This is called hormesis, the tolerance to toxicity is produced by the injection of a toxin. In Kings Cross where the toxicity of risk is made plain, the denial of risk is a denial of learning. The denial of learning is a denial of life.

So, in the zero harm culture that focuses on band aids and minor risks, nothing is said about the damage caused to tens of thousands of Australians who are harmed by the practices of FIFO and DIDO . So, in just one example we see the zero harm ideology fall over as a selective convenience and delusional denial of living. Even in the supposedly compromised position of ‘toward’ or ‘aspirational’ zero harm we see the language of perfection further disconnect itself from the realities of risk in everyday life, work and living. There can be no living without uncertainty and no learning without risk. The aspiration for perfection in itself is divisive in its language, priming workers to deny fallibility and frailty and inviting punishment for minor mistakes. Workers are not ‘problems’ to be solved or statistics to count but rather ‘people’ to be met.

Do you have any thoughts? Please share them below