What Can Marx Say to Safety?

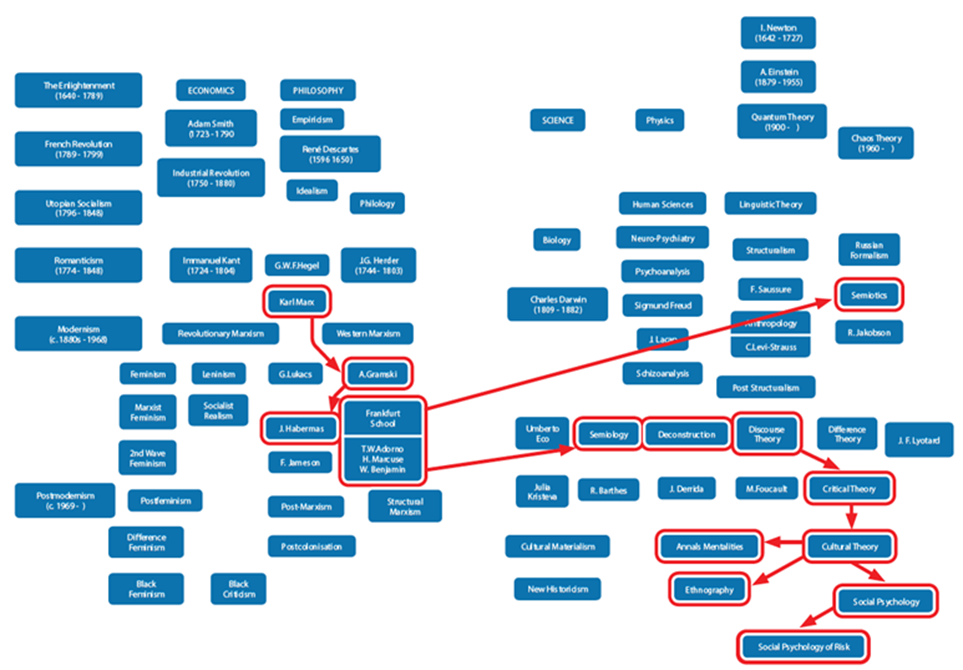

It’s important to understand that the Social Psychology of Risk (SPoR) emerges from traditions in Marxism, Post-Structuralism, Semiotics and Deconstruction. This is represented graphically (semiotically) as follows:

Marxist and Post-Marxist theory is most observable in Critical and Cultural Theory and plays a significant role in an SPoR approach to Feminism, Ethics and Politics.

However, understanding Marx is not just for those in Social Psychology. It is considered essential for any profession to consider Marx in relation to: service, justice, ethics, helping, social politics or economics. Whether studying Law, Medicine, Education or Nursing professions, a dip in to Marx is considered helpful for understanding the nature of power, ethics and justice. For example, in Education and Teaching professions an understanding of Critical and Cultural Theory is considered essential for understanding pedagogy, schooling, institutions and learning. In studies in Ethics, Justice and Law it is considered foundational to understand Marxist and Post-Marxist Theory. When it comes to ethics, safety, risk and justice Post-Marxist theory doesn’t makes the reading list.

Marxist theory was strongly influenced by a Hegelian view of History and dialectic. A Marxist dialectic is premised on the social relations (forces) between: power, material, capital, labour and production. Marx called the dynamics between these ‘forces’ Dialectical Materialism. In many ways Marx understood these ‘forces’ as having a power unto themselves. That is, they each had an inbuilt power (dynamic) that not only reproduces itself but in the process, alienates persons/humans from themselves. This alienation is the outcome-as-by-product by the desires of the ruling class and the powerful. It is important not to confuse Marxist/Socialist theory with communism.

What we learn from Marx is that power embedded in the forces of: material, capital, labour, power and production ends up driving the oppression of the weak and vulnerable.

When we explore the challenges of risk in the workplace and who is privileged by social arrangements we quickly find that those with the most power sustain systems to their advantage. Once the powerful sett sources of power in place, they take over under their own dynamic, similar to who Jung describes archetypes (https://academyofideas.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/71.-Carl-Jung-What-are-the-Archetypes-Quote-Book.pdf).

The powerful develop myths (embedded in symbols) in work that sustain the dehumanization of the vulnerable, overpower the powerless and brutalise personhood. The power and structures of oppression of the vulnerable are maintained through myths, symbols and ideologies that shape the way work is undertaken. Resistance and questioning of dominant ideologies must be quashed and demonized. (sound familiar?) Zero is one such ideology that turns people into objects and numbers to be measured and controlled. If Marx was alive I can see him smashing the ideology of zero as a mechanism for brutalism, alienating workers and fostering the love of bureaucracy.

Marx called ideology ‘False Consciousness’. Ideology for Marx was defined as ‘the set of ideas and beliefs that are dominant in society and are used to justify the power and privilege of the ruling class’. The dominant rule of this ideology then transforms into a hegemony, where a culturally diverse society is dominated by the ruling/powerful class that manipulates the culture of society.

There are numerous places to read Marx, perhaps this is the place to start:

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Selected-Works.pdf

https://www.bard.edu/library/arendt/pdfs/Marx-CommunistManifesto.pdf

http://digamo.free.fr/heinrich.pdf

http://fuchs.uti.at/wp-content/uploads/introduction.pdf

Rich Lawrence says

Sorrow, sickness, pain and death, and mere wear on the body are inherent in existence. They are amplified by labor. Even, say, if you owned your own self-sufficient farm, there would be many risks of injury. What is different in the capitalist system of social production is that the worker never owns the product, and that both absolute surplus value (from extended working hours) and relative surplus value (from increased productivity i.e., speeding up the line) are causes for increased occupational illness, injury and death. There is strong evidence of this. Citation needed? It’s kind of common knowledge. Two amputations a week are the cost of working in a US meat packing plant. So I can show a direct link to profit (surplus value) and occupational sorrow, sickness, pain and death. That is the easy part.

The more difficult part, that I want to do in my writing, is show how the very real (concrete) illness, injury or death is also a concrete alienation of the worker from their ability to work or even be alive, literally separated from their life, and connect this concrete to the theoretical alienation that stems from never owning the product.

Before I write that section, I want to get the theory correct. So I am asking, when you have a moment, to either just tell me what you think, and I will believe you, or direct me to some reading that might help. Thank you.

The worker becomes poorer (in health, in wholeness, in life) the more wealth he produces, the more his production increases in power and size. The worker becomes an ever cheaper commodity (in terms of wages goes down, in terms of health risk goes up) the more commodities he creates. The devaluation (in many aspects) of the world of men is in direct proportion to the increasing value of the world of things.

Labor produces not only commodities (products); it produces itself and the worker (here, the worker is the worker’s life, health and wholeness) as a commodity (for sale) –

(here Marx clearly delineates labor as a commodity and the worker as a separate commodity) – and this at the same rate at which it produces commodities in general. (Note the word “rate.” This means that the labor and the health etc. of the worker is consumed at the same rate at which they produce the commodities.)

This fact expresses merely that the object(s) which labor produces – labor’s product(s) (note there are at least three, labor itself, the product, and illness and injury that will occur)

– confronts it as something alien, as a power independent of the producer.

The product of labor is labor (and the workers health, etc.) which has been embodied in an object (the product), which has become material: it is the objectification of labor. (and the objectification worker’s sorrow, sickness, pain and death) It’s realization is its objectification. Under these economic conditions this realization of labor (the creation of the product and the creation occupational illness) appears as loss of realization for the workers (they do not own the product and they do own the amputation, illness or death) objectification as loss of the object (the product) and bondage to it (it means the “product” of the labor that the worker does own, the resultant damage to their bodies for life) appropriation as estrangement, as alienation.

Rob Long says

Hi Rich, not exactly the best space to reply but there are aspects in what you are thinking are helpful. Ricoeur stated the following:

(1) Man takes note of his means and hence of the autonomy which

he has thanks to the possibilities of action. He does not see this as progress or freedom but as a charge or burden, as a kind of condemnation.

(2) Man has the means to assure his well-being. These are not regulated, however, by true well-being, by consumption and distribution, but by a desire for maximum well-being, an inauthentic increase of needs, an infinite and indefinite desire, an ability to destroy the fruits of accrued creativity, with not the least response to his situation.

(3) Man has the means of power which enable him to exercise almost absolute control and this makes him want to manipulate everything. We wish to alter the human condition, to annihilate distance in space and time, to prolong human life indefinitely, to control both birth and death. We impose on every aspect of life a type of existence borrowed from the technical model and we place all beings in a relation which brings them within the sphere of what can be manipulated and utilized.

Ellul also stated the following:

Four aspects of experience may be distinguished:3 (1) the experience of the powerlessness of each of us in face of the world, of the society in which we are but which we can neither modify nor escape; (2) the experience of the absurd, of seeing that the events we have to live through have no meaning or value, so that we cannot find our way in them; (3) the experience of abandonment, of knowing that no help is to be expected, that neither others nor society will grant any support, the idea of dereliction which is so dear to existentialism; and finally (4) the culminating experience of indifference to one¬ self, in which man is so outside himself that his destiny is no longer of interest to him and he has neither desire nor zest for life.

I also wrote this:

https://safetyrisk.net/freedom-in-necessity/

This is also from my book Real Risk:

Alienation

Relevant research on alienation and engagement is provided by the eminent French sociologist, Jacques Ellul. Ellul’s work The Ethics of Freedom (1976) seeks to define the anthropological nature of educative discourse and discusses the nature of alienation as a part of the total human condition.

Ellul’s concept of alienation extends the materialist perspective of alienation by adding an ethical aspect (1976, p. 25).

Man is alienated because, once launched on the venture of exploitation in which he no longer acts justly, he is obliged to view everything with a corrupt conscience and to create an ideology which will conceal the true situation. His religion is the most complete and misleading ideology. It is here that he is most completely divested of himself. This is partly because, as in Feuerbach, he dreams up an illusory supreme being out of all that is best in himself, out of his own worth and righteousness and goodness. He transfers these to the Absolute. He thus robs himself by the projection. Partly, however, it is also because man expects liberation from someone else instead of himself. Religion is the ‘opium of the people’ because it impedes action by causing man to transfer his own possibilities to another being.

Alienation according to Ellul is caused by a frustration in the human search for meaning. This frustration

is generated by exploitation and a created ideology that masks real meanings of existence. The assumption underpinning Ellul’s perspective is that humans cannot escape alienation in their own capabilities. He argues that alienation is a material and spiritual disorientation. This spiritual dimension is clearly out of step with a Marxist- materialist perspective. Whilst the materialist argues that alienation is the:

. . . separation of humans from those things that they need in order to lead fulfilling lives (Cormack, 1996, p. 7)

Ellul argues that alienation means:

. . . being possessed externally by another and belonging to him. It also means being self-alienated, other than oneself, transformed into another. (Ellul, 1976, p. 24)

Chapter 6: Glossary 123

In a curious twist this implies that alienation is developed through the handing over of oneself, ones meaning in life and ones purpose to another (person, power or ideology). This means that alienation is really self alienation

or alienation from what it is to be truly human. Ellul therefore argues that the more humans try to control

their lives in self preoccupation the less they become masters of it. Such efforts are apparent in the process of institutionalisation. He argues (Ellul, 1976, p. 29) that there are four aspects of the alienation experience. These are:

1. the experience of the powerlessness of each of us in face of the world, of the society in which we are but which we can neither modify nor escape

2. the experience of the absurd, of seeing that the events we have to live through have no meaning or value, so that we cannot find our way in them

3. the experience of abandonment, of knowing that no help is to be expected, that neither others nor society will grant any support, the idea of dereliction which is so dear to existentialism; and finally

4. the culminating experience of indifference to one-self, in which man is so outside himself that his destiny is no longer of interest to him and he has neither desire nor zest for life.