Originally posted on August 7, 2016 @ 3:21 AM

So you reckon you can calculate risk to 3 decimal places?? Think again. A recent article by Dr Robert Long, that may make you rethink your belief in Risk Assessment as being objective!. If you liked this article then you should read the whole series:

Extract:

Finally, we should be self-reflective about our assessments and be prepared to admit our bias, as we invite the view of others into our decision making. Once you know that your auditing is biased you are then enlivened to the fact that you could be sometimes be wrong and that even the participation of those being audited in the process might be a valuable strategy.

Objectivity, Audits and Attribution

I made the mistake recently of suggesting to a group of risk managers that a discussion about the myth of objectivity was overdue. I was blown out of the water with the response that such a discussion was irrelevant! They all knew what they were doing, were experienced and had extensive audit tools to ensure objectivity was their reply.

(Just a quick warning, the next paragraph is a bit academic but stick with it so you can get to the Risk Ranking Activity at the end.)

Unfortunately, objectivity is a myth. The myth was dismantled by Michael Polyani in 1946 in his publication Science, Faith and Society and by Thomas Kuhn in 1962 by the radical book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. It was shown by Polyani, Kuhn and now a host of postmodernist thinkers (Heidegger, Foucalt, Derrida and Baudrillard) that the positivist accounts of history and science could not be separated from the humans who participate in such accounts. It was the work of the Frankfurt School that showed that all communication is infused with politics, power and disposition. Indeed, the postmodernists argue that a lack of participation in the process of analysis robs any communication of commitment and intimacy with the subject. The reality is, all data is interpreted and our interpretations rely on a host of cognitive, social and sub-conscious biases.

Any assessment of risk is an emotional, arational and subjective exercise. Risks are not objective but are ‘attributed’. One person is anxious about one activity when the person beside them is not. Some people are confident with some high level risks and others are much more cautious. In Risk Makes Sense a table (p. 33, 34) was presented and discussion (Is Risk Neutral) showing how various human biases aggravate or mitigate risk attribution. The idea that humans assess risk objectively or just calculate risk based on the common criteria in any risk matrix (exposure, frequency, probability and consequence) is not supported by the evidence.

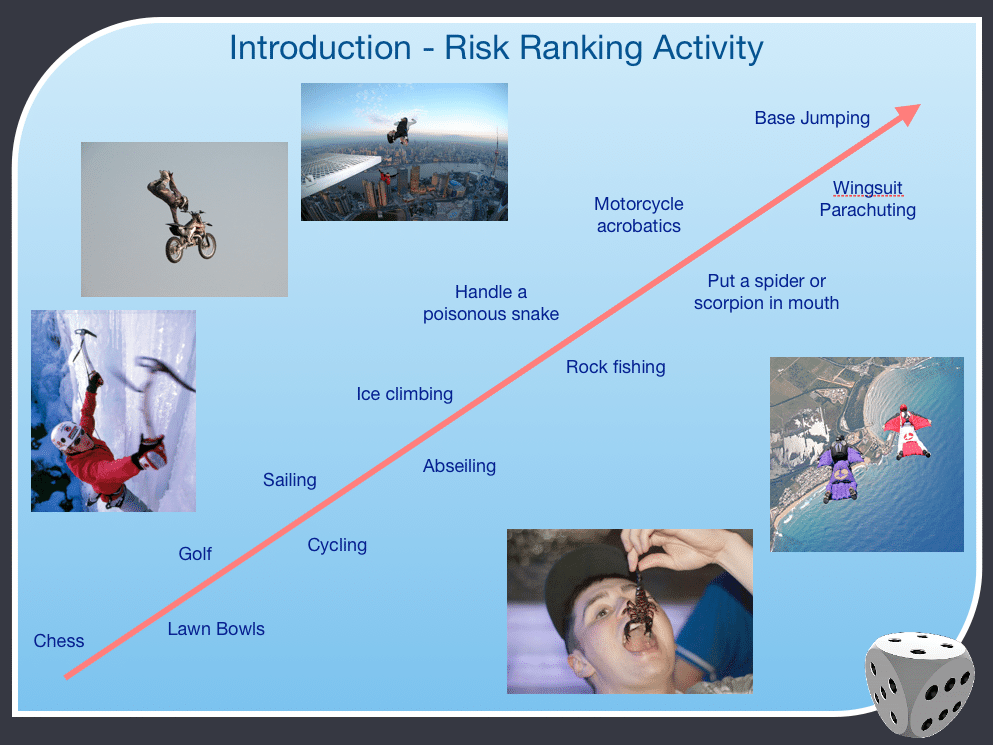

One fun exercise I like to do in any worksite induction is to draw a line on a white board and to get everyone present to introduce themselves by placing their name beside the highest risk activity they would be prepared to undertake. See Figure 1. This is not only a fun way of getting to know people in the induction group but shows instantly how everyone in the room attributes risk differently. Then each person in the group explains where their risk threshold is and gets a chance to explain their understanding of risk. In this way in less than 20 minutes everyone has shown everyone in the group how Risk Makes Sense for them. This not only blows away the nonsense of ‘common sense’ but raises the bar for the importance of safety conversations with others. (You are more than welcome to take this idea and use it in your next induction, tell me how it went.)

We know from socialpsychology that the way we attribute risk to various activities is in part affected by many cognitive biases. The ‘availability heuristic’ and ‘probability neglect’ are two mechanisms that powerfully affect the way we attribute risk. Depending what is ‘available’ to our memory or our senses we magnify, distort or dismiss the value of certain risks. We neglect the probability of something happening depending how distant our emotions are from the subject. This is also called the ‘recency effect’, people tend to overestimate risk if their experience of an event is more recent and personal.

Humans are emotional creatures and when fear and anxiety are intensified people focus on the adverse outcomes more than the likelihood of that outcome occurring. This intensifying of emotions is where much human risk aversion originates. If you put this emotionally charged perception in crowds or through the media then mass hysteria and groupthink further distort the real assessment of risk. You then find the general population becomes fearful of prowlers, immigrants, Islam or community violence even though its incidence id decreasing. The problem is that availability and attribution factors make people fearful when they need not be fearful and fearless when perhaps more caution is required.

Figure 1. Snapshot of my Induction Risk Ranking Activity

So where does the myth of objectivity leave us with auditing and assessment? They key is social awareness, communities-of-practice and self-awareness. Lone audits and assessments are OK, but don’t think you are somehow superhuman and objective. There should not only be ownership in risk by workers, there should also be ownership in risk by auditors. The more we try to ‘step away’ from something to try and be objective about it, the more we reduce our participation in ownership ‘with’ the subject.

All checklists are developed within the biases of the developers of the checklist. Sometimes its good to think beyond the checklist, the checklist is often the minimum in thinking, checklists can be very constraining to open and critical thinking. The last couple of incident investigations I was on indicated that the incident was caused as a result of people not perceiving factors that were not on the checklist. Of course the solution by the crusaders for bureaucracy is to simply increase the size of checklists. Increasing checklists doesn’t of itself increase the capability of people the think critically. Indeed, the ‘flooding’ of people with checklists sometimes induces the opposite, learned helplessness.

It also might be good to bring outsiders and novices on audits and assessment walks, just because they don’t think like you. There is nothing more dangerous to an audit or assessment than the problem of ‘confirmation bias’. We all like to have the agreement of others and the back slapping that enshews but this also limits our capability to think ‘outside the box’. Maybe the apparently ‘dumb’ questions of others unfamiliar with your auditing bias are just what you need, particularly if you have been doing the same auditing processes for some time.

Finally, we should be self-reflective about our assessments and be prepared to admit our bias, as we invite the view of others into our decision making. Once you know that your auditing is biased you are then enlivened to the fact that you could be sometimes be wrong and that even the participation of those being audited in the process might be a valuable strategy.

Do you have any thoughts? Please share them below