Have Cake and Eat it Too

One of the fascinating outcomes of the Zero Vision Global Safety Congress was The Occupational Health and Safety Professional Capability Framework, A Global Framework for Practice . What is most interesting is to read the use of language in this document. The purpose of the Accord (p.5) is to:

‘The Singapore Accord is a call to action. It is collective action by the leading OHS professional and practitioner organisations from around the world, supported by INSHPO, to commit to the Global Vision of Prevention through the adoption of a global framework for practice. Such a framework seeks to uphold high standards of competent health and safety professionals and practitioners in creating healthier and safer workplaces’.

What is interesting in this document is the effort made create a distinction between a ‘professional’ and ‘practitioner’ and then use both words interchangeably throughout the document.

Interestingly the development of acknowledgements (p6, point 4) states:

‘That occupational health and safety professional and practitioner knowledge and skills must be evidence-informed and based on strong scientific and technical concepts’.

So, the choice is the frame up the notion of safety people though a STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) worldview. How strange when many of the goals stated in the Framework seek to be people-centric.

In clarifying the role of the safety person the document then uses the language of ‘safety specialist’ (p.10). In clarifying the OHS ‘role’ the ‘safety specialist’ is described as a ‘problem solver’. Then the document states:

‘Concomitant with the changing role, soft skills, including coaching and the ability to work with organizations at different levels of cultural maturity, are appearing as skills in demand for OHS Professionals and OHS Practitioners. Terms such as “soft skills” and “coaching” are vague and are better understood from the perspective of relationship building. The ability to build a web of relationships enables the OHS specialist to influence others to bring about change in organizational practices focused on risk control, which, in turn, should allow the organization to move up the safety culture ladder.’

How interesting. I wonder how safety is going to do this from a STEM base and in a document that hardly ever refers to people and spends most of its language speaking about tasks, hazards and risk?

The word ‘people’ is mentioned 18 times in the document but rarely as the subject of discussion. Mostly the word ‘people’ is used to describe capability, a group or the focus of harm. The word ‘hazard’ is used 84 times. Tell you something?

The Distinction between OHS Professional and Practitioner is made (p.10) states:

‘While the workplace may have a range of OHS roles, two clear categories exist:

the OHS Professional, who is usually university educated (or has attained a similar level of higher education), and

the OHS Practitioner, who is usually vocationally educated.’

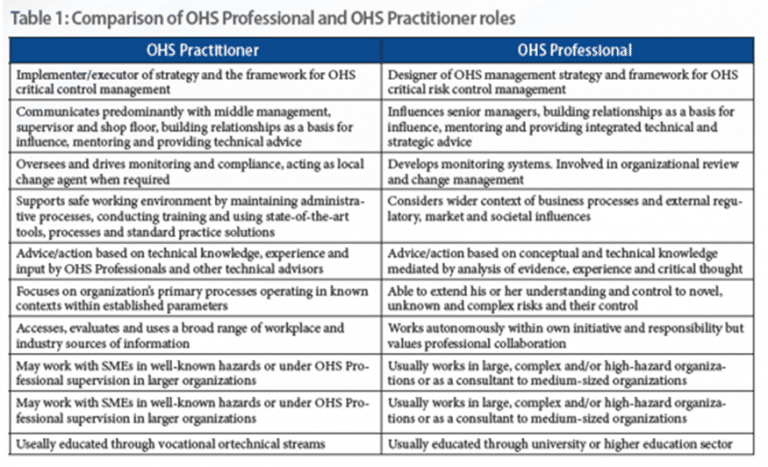

Then the document lists two tables indicating the qualitative and quantitative differences apparently between ‘roles’.

The distinctions are tabled below (p.11):

Then these distinctions are further elaborated on page 12 and 13 of the document but then the document slips into the global use of the term ‘safety specialist’ to designate both ‘professionals’ and ‘practitioners’. In that discussion on page 12 the activity of safety is compared to the professionalization of nurses. What an amazing comparison when the education and accreditation in those two sectors simply bear so little comparison in critical thinking, professionalism, preparation for work and transdisciplinary study.

One of the distinctions in all this language in the document is that if one uses the word ‘professional’ and links it to safety then it must be so. The seduction to throw around the word ‘professional’ in the safety sector is amazing. The word is so commonly used as an adjective of safety as if the qualities and characteristics of professionalism are just assumed to apply. By any measure safety is not professional and the word simply should not be applied to the activity.

https://safetyrisk.net/professional-challenges-for-the-safety-industry/

https://safetyrisk.net/safety-and-risk-professionalisation/

I guess the language of this document shows the problem with using such language anyway. From page 13 onwards in the document the words ‘safety specialist’, ‘roles’, ‘professional’ and ‘practitioner’ interchangeably to indicate the same person and the same action. The crossover is profound between various descriptions that it is quite a strain to even tell the difference between the two. For example (p.28)

‘A conceptual framework together with specific technical knowledge is essential for both the OHS Professional and OHS Practitioner. Such a knowledge base supports innovation, flexibility and openness to new and advancing thinking about OHS. It enables OHS specialists to develop and adapt their professional practice to changing demands of business and society and also enables them to mentor and develop others.’

What is significant in the document is an absence of discussion on the definition of being professional itself. The focus of the Accord is on doing and simply assumes that safety possesses the commonly accepted characteristics of professionalism. I discussed the many characteristics absent in WHS in my paper https://safetyrisk.net/professional-challenges-for-the-safety-industry/. This discussion in my paper demonstrates that many of these characteristics of professionalism particularly in education and ethics, are completely absent in the sector. Just the fetish with zero alone so clearly enshrined in the World Congress, is demonstrably unethical and prohibits safety from being understood as a profession. The nonsense language of choice, demonization of being human and fallible, blame, focus on objects and fixation on counting also demonstrate that safety is neither ethical nor ‘professional’. You certainly don’t get any such nonsense discourse in nursing. Just imagine how long the nonsense language of zero would last in a hospital or ambulance.

The ‘forced’ nature of the professional/practitioner distinction in the document is clearly strained, divisive, blurred and at best ‘splitting hairs’. I wonder why so much is invested in such a distinction and for what purpose? Maybe a better way forward is not to use the language of ‘professional’ or ‘practitioner’ at all but simply to adopt the language of the Accord itself and use the term ‘safety specialist’.

Do you have any thoughts? Please share them below