Originally posted on August 15, 2016 @ 4:38 AM

Introduction

Neuroscience research has revealed that our brains account for approximately two percent of our body weight, but consume about fifteen percent of our cardiac output, twenty percent of our total body oxygen and approximately twenty-five percent of our blood sugar. They are built up of hundreds of billion cells and each cell is as complex as a large city. There are in fact as many connections in a single centimetre of brain tissue as stars in our galaxy. It is quite simply the most complex thing in our known universe.

Our hopes, dreams, aspirations, fears, instincts, fetishes, desires and safety all derive from this three pounds of pink fleshy matter.

Yet this complex beast is in fact too powerful for its own good and leads us into uncertainty and danger sometimes without us even knowing it!

Most of what we do, think, feel is not under our self-control, as our brain mostly runs the show below the security of our conscious minds.

And, in an age where our brains are inundated with facts, figures and opinions (do this, do that) are relentless and this makes the job of our brains even harder. In fact, the message seems to be that, if all possible, we should avoid risk at all times. But that makes are world very boring and can often lead people into danger. The trick is therefore to take risks that will benefit us rather than ones that will ultimately kill us.

What Science Tells Us

Research shows that one third of our brain is devoted to vision and yet only a small percentage is in clear view (approximately the size of your thumb). Our sight is about as good as looking through a dirty shower door, but has the illusion of us seeing a two hundred and seventy-degree panoramic clear view of life ahead of us. This false vision goes along-way to explaining why we have the colossal number of road accidents each year.

Our brains computes information on a need to know basis and fills in the blanks. In fact, what we perceive is not a true indication of what we really see or believe. Our brain is so powerful that it is constantly arbitrating a battle between conflicting information and often makes instantaneous decisions based on heuristics rather than mathematical equations we use to calculate risks.

|

Necker Cube

Stare at the cube for a minute and see what happens? |

If you look at the night sky, you can fit seventeen moons into your blind spot and your brain instantly invents a patch to fill in the space. Every day we are not actually seeing what’s out there, we are simply perceiving what our brain tells us to see. So when undertaking a safety inspection don’t do it on your own but as part of a team, ideally with employees with different jobs and experience (including some front-line workers) It’s good to involve workers, because people won’t buy into something unless they have weighed in first.

Research also shows that there is also a huge chasm between what your brain knows and what we are capable of thinking and implicit memory is completely separate from explicit memory. This has been proven by studying people with amnesia who improve their performance after playing several hours of intermittent video games and filling partial words in a sentence even they have no recollection of it being read to them. These studies show that the brain can be subtly manipulated to change beliefs and lead to safer interventions.

Studies suggest that are brains are reprogrammable (we can teach old dogs new tricks) and technology is now available to even allow blind people to see through their tongues.

“Man is equally incapable of seeing the nothingness from which he emerges and the infinity in which he is engulfed.” – Blaise Pascal

In the Truman show the eponymous Truman lives in a matrix completely constructed around him and he accepts everything including his surroundings as real.

What if our traditional safety systems and programmes, which were adopted and are virtually unchanged since the early seventies are mirrored in a similar fixed Truman society, which is totally alien and out of alignment with our technological world we live in.

Research suggests that the function of our brains is to generate behaviour that is appropriate to our surroundings and evolution has carved out our character, thoughts and beliefs over time. The problem is that our health and safety systems haven’t evolved at all and potentially become a dinosaur of our modern times.

However, I can understand why as rubbing against the grain can be a perilous exercise when bosses have spent thousands of dollars to build immense bureaucracies to control people and stop them making mistakes, that people more than often make bad judgements and behaviour has to be forged through rules, rewards and punishments. But efforts to reduce accident rates have plateaued and no matter how hard we try, these conventional systems have done no more than regurgitate strategies with different slogans and excessive hype.

What we should be asking is not what system is required to change the nature of health and safety, but rather what is required to change the nature of the work?

And, where else to initiate it than New Zealand and place where we have more innovative thinkers than anywhere else in the world. Don’t get me wrong the no.8 wire mentality has led to many accidents in the past, but by tempering it with a structured approach (to a slightly larger diameter), I honestly believe we can be world leaders in health and safety. We have the ability to zig more when everyone else zags.

Risk Identification

Safety systems such as JHA’s, Risk Registers, Hazard Identifications try to force us to fit everything into a series of rectangles which nicely fits an A4 page!

Sadly, the “Boxification” of procedures has led us up the garden path to a compliant place where we feel comfortable with mediocrity and have lost sight of our dreams and aspirations.

The very nature of these systems has reduced our ability to spot scotomas and our once vivid and imaginative minds have given way to a tick and flick society.

It’s in these plain old white narrow boxes where we are forced to solve risks and record all meaningful information, but in fact it does nothing more than lure us away from reality.

In these white boxes, we often get polarized by subjectivity and fail to account for the competence, experience and ability.

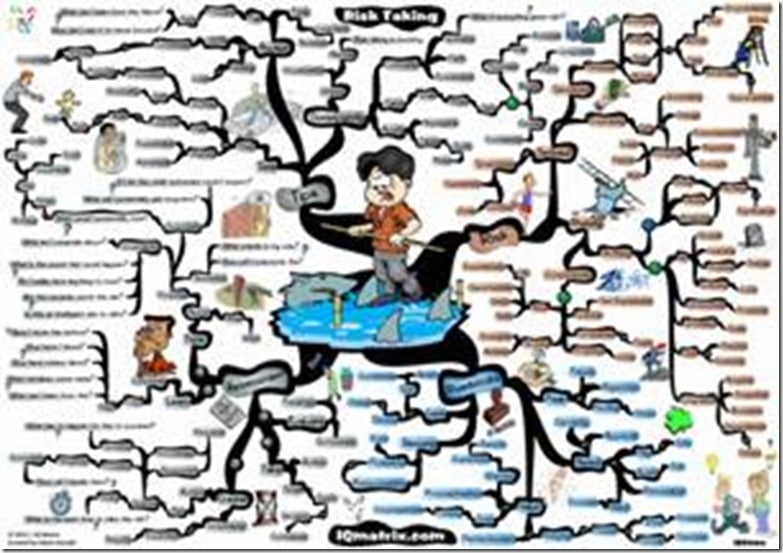

Our brains don’t think in boxes but in a series of associations, so a mind map would be a far better medium to improve our thinking and devise better solutions.

The boxification of procedures has prevented everyday people from overcoming their limitations, possibly increased risk through boredom and stifled growth by blocking out creativity.

It’s not the number or size of boxes in your procedure that matters, but what you do inside them that counts!

If we really want to make real big dent in workplace incidents, it’s perhaps time to change from our conventional methods to more divergent systems, utilizing new technology to process and record information, which will allow people to pursue their highest goals and aspirations and make the world a truly safer place?

Considering on what has been learnt so far this is extremely difficult based on our brains limited capacity to remember things in the past. Perhaps what people need is a prompt to think about hazards by categorising them into distinct topics (see diagram below).

And, when recording the information, we suggest using a mind map to document the outcomes, which is similar to how the brain remembers and stores the data.

Risk Assessment vs Rule of Thumb

At school we are taught the mathematics of certainty and trigonometry, but never the statistics of uncertainty. In biology we are taught the rules of evolution, but not the fears and desires of psychology. In health and safety, we rarely receive training on the risk assessment and risk communication.

Throughout history we have created a belief that systems create certainty and this is supported by the insurance we take out on homes, the horoscopes we read in the daily newspaper and what we read on google. The fact is our lives are very uncertain and ever changing.

“In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” – Benjamin Franklin

When assessing risk, we are told to multiply the likelihood of an event occurring by the consequence of the probable injury (law of cause x effect) to calculate the magnitude of the outcome. The fact is our brains don’t evaluate risk like this and everyone’s perception of risk is slightly different. The very subjective nature of second guessing risk using this process can even increase injuries by bracketing hazards into the wrong category.

Imagine the reverse of these three playing cards below contain an ace and two kings

If I asked you to pick one and you chose card 1, what is the probability of turning over the ace – 1 in 3 or 33.3%.

If I then turned over card 2 and it revealed a king what as the probability that card 1 is the ace?

Your answer would probably be 1 in 2 or 50%, but you would be incorrect and that’s why we find it hard to calculate risk. The correct answer is 2 in 3 (66.6%) if you switch and only 1 in 3 (33.3%) if you stick with your original choice.

The problem is not simply inside the human brain but in the way the information is framed. When assessing risk, we shouldn’t think of risks in isolation but in multiples.

In Risk Savvy, Gerd Gigerenzer suggests likelihood has three elements – frequency, physical design and degrees of belief.

Frequency is about counting, but in order to more accurate it needs to balance the probability of risk in foresight with what is actually achieved in hindsight. Comparing the perceived frequency with the actual output of how many times it occurs.

Physical design involves constructing something to mitigate the risk upfront. If we can encourage architects and engineers to design out risks in buildings and machines, then the calculated output of risk would be significantly lower.

Degrees in belief is based on anything from experience to personal health and can vary from person to person, but should be factored into the overall risk calculation

F (frequency) x P (physical design) x D (degrees in belief) = Likelihood x Consequence = Risk Level

Using this equation, it could be easy to get sucked into thinking that one tool fits all and be fairly confident of calculating risk more accurately. However, it is still quite subjective relying more on judgement than fact and a better measured of risk indeed could indeed be gained by looking at the outputs (health and safety statistics) as long as they are accurate?

The fact is our lives are very uncertain and often difficult to assess, therefore perhaps another, far simpler rule might be more effective when calculating risk?

What Comes First the Chicken or the Egg?

We often here a comment such as “follow your gut” when people are told to make instinctive decisions. In fact, rules of thumb and intuition have been vital to the risk assessment process since the dawn of mankind and are still very prevalent today.

When in a dangerous situation, what comes first the psychological aspects or the physiological effects? In other words, when we feel a strong emotional response to a risky job do we feel fearful mentally and set off our gut response, or do we get a gut response first and then interpret the response as fear?

In a study undertaken by two researchers Schachter and Singer at Columbia University they injected volunteers with adrenalin but instead told them it was a vitamin called ‘Suproxin’ and explained the purpose of the study was to see how it would affect their vision.

Shortly after the injection, the volunteers were paired up with another person (an insider) and asked to fill out a questionnaire. The inside sometimes clowned around and on other occasions acted very angry. The study was in fact to figure out the interplay of body and the mind.

The results of the study showed that those volunteers placed with the clown felt cheery and behaved happily whilst those paired up with the angry person became angry themselves. The outcome indicates that the way we feel emotion is contrary to what we believe. It is in fact gut feeling that comes first and thoughts are added on afterwards.

And, if this is true and are minds are led by our bodies, what are the implications for safety and assessing risks?

We spend so much time trying to calculate risk and in doing so this reduces our time thinking of better controls to eliminate or mitigate the hazards. The NZ Work and Safety Act 2015 requires companies to determine which risks are significant risk, but not necessarily to quantify risk. Using a simplified approach to categorise risks into high, medium or low categories may be more effective an accurate than using a risk matrix.

Indeed, one of the significant changes to the new Act encourages everyone to take a more constructive role in promoting improvements in workplace health and safety practices. Not just to ensure that workers gone home safely every day, but safer and healthier every day. To achieve this, we can’t continue to live in the past, we need to think outside the box and try out some alternatives which are more aligned with the way humans operate.

Analysing Risks – What to Assess and Look Out For?

In a study carried out by the University of Canterbury observers watched drivers who passed beneath a bridge to see how and where the drivers held the steering wheels, the speed of the vehicle measured with a radar gun and the travelling distance from the car in front.

The statistics showed that 80% of drivers had at least one hand on top of the wheel, but only 25% of drivers were holding the wheel with both hands. And, drivers who had two hands on the wheel were twice as likely to be female who drove slightly slower compared with one handed drivers.

Also, those drivers with two hands on the wheel drove further behind the car in front (60m), compared to 52m for one handed drivers.

Another cause of road accidents is our ability to overestimate our driving skills. In a study undertaken by the DVLA in the UK, speeding drivers were sent a questionnaire to complete asking how many crashes they had been involved in and more than 10,000 motorists responded.

On average they had been involved in a crash every four years since learning to drive. Also, comparing national speeding results at accident scenes was even more revealing. For every 1% increase in speed there was a 13% increase in the number of crashes on motorways, and an 8% increase in crashes on other roads.

So, if the average speed on a section of a motorway was 70 mph, a driver travelling at 72 mph would not crash every four years but every three years.

If this is the case, what factor can be added for one handed drivers travelling at a distance of 52m behind a car instead of 60m?

So when analysing your incident statistics instead of looking at ‘What’ cause the accidents, you should perhaps look at ‘Who’ caused them and how often.

Communicating Safety & Rewarding Performance

When completing and communicating most safety documentation we generally undertake it prior to the job commencing at the start of the day. But, is this the most effective and memorable way to get people to retain the information and apply the rules?

Think of the last time you completed a safety form or listened to a safety briefing. How much did you remember, how much went in one ear and out of the other. How effective was the orator delivering it and how much of it did you apply to the job?

Is up front safety the best way to relay and retain safety knowledge, or is there a better and more powerful way?

As parents we often implore our children to prepare for their exams up front well ahead of exams instead of waiting until the last minute, but what if procrastination or post reviewing was far more powerful than planning up front?

Procrastination may be seen as the enemy of productivity, but in a controlled form can be the resource of creativity and improvement. In fact, some of the most influential thinkers and inventors in history have been procrastinators such as Leonardo da Vinci, Martin Luther King Jnr, Thomas Edison and Abraham Lincoln.

Adopting and sticking to traditional safety systems we have closed the door to other perhaps better alternatives? However, great leaders don’t skip the planning process, they procrastinate logically making lots of incremental changes, testing and refining the process continually, always looking for improvements.

Karl Weick describes it as “Putting old things in new combinations and new things in old combinations.” What he is saying is “Learn from what you discover in your audience on the canvas, or in the data.”

So the next time you plan to fill in a safety form or deliver a speech consider doing it incrementally throughout the day. And, seek honest feedback on what could have been done better and how it can be achieved?

We don’t start life as a blank slate, as our brains come pre-bundled with basic software to use the day we are born. However, our brain has trouble with number type calculations that it didn’t evolve to solve. Instead it uses associations to solve social issues.

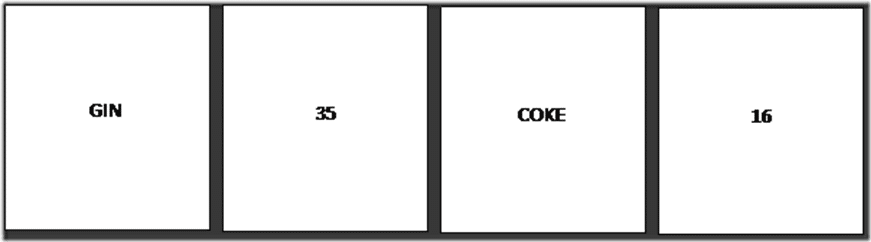

Take a look at these four cards. If I told you that if a card has an even number on one face, it has the name of a primary colour on its opposite face, which two cards do you need to turn over to assess whether I’m telling the truth. The answer is the number eight and the yellow card.

The fact is our brains aren’t wired for binary logic because we evolved without needing to nail specifics down to finite decisions.

Now take a look at these different cards. If I now told you that If you’re under eighteen, you can’t drink and drive, which two cards do you need to turn over to establish if the rule is broken? You probably came up quite easily with the answer sixteen and the gin cards.

The two puzzles are formally equal, but the second one is far easier because it uses social interaction (such as detecting cheaters) to solve problems rather than linear thinking. That’s why when we write a job safety analysis it very rarely transpires into what we do on the job.

When we read in books, we actually convert the words into images to build a story of what we perceive, so perhaps a more effective way of remembering safety documentation is to covert the steps into a series of interlinking mnemonics.

If I offered you $200 today, or $210 next week, which one would you take? Most people would choose the first option as it appears more worthwhile to take the money now rather than wait seven days for the extra $10.

However, If I were to offer you $200 fifty-two weeks from today; or $210 fifty-three weeks from today, which one would you take? In this scenario most people tend to go for option two because they discount the future option. So if rewards closer to home are valued more highly than those in the distant future, safety targets and pay-offs need to be set for weekly objectives rather than ones for achieving an LTIFR reduction once a year. And, even a pat on the back for working safe can be immensely powerful if done frequently.

Focusing on the Positives

Whilst trying to navigate to India, Christopher Columbus underestimated the diameter of the global and accidentally found America. Our current health and safety systems are marooned on an island and although they prevent people falling off the edge, they do very little to encourage innovation and positivity. They provide a zero negative error culture with a fear to make errors with little chance of improvement. What we need to do, is to balance risk with resilience making errors more transparent and instead of investigating accidents, let the people know what happened and ask them for improvements.

SAFETY IS NOWHERE

Primitive man evolved to eat, have sex and avoid fear and our brains still operate in this mode when making on the spot decisions on autopilot. So what we need to do is make our safety systems more attractive (sexy) and positive without the fear of blame when things go wrong. We need to be more strategically optimistic instead of defensively pessimistic.

Strategic optimists anticipate the best, stay calm and have high expectations, whilst defensive pessimists except the worst, feel anxious and imagine all the things that could go wrong. They intensify the anxiety and convert it into motivation. Once they’ve considered all the that could go wrong, they are driven to avoid it, considering all the alternatives so things don’t crash.

“Courage is not the absence of fear, but triumph over it.” – Nelson Mandela

So when there is an incident, perhaps we need to stop searching for those people who might have caused it and instead go searching for the people who have never had an accident and find out why?

And, when things go well, keep thanking people for their cooperation and involvement (pat them on the back) in order to foster an improved safety culture.

Measuring Safety

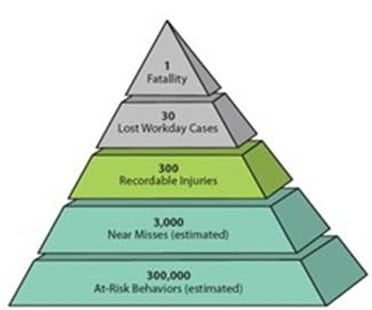

At the end of every Adele Concert whilst she sings ‘Rolling in the Deep’, 128kg of confetti is dropped on the audience. This equates to 28,000 sheets of A4 paper and when each piece of paper is cut into 10, this converts to approximately 300,000 pieces of confetti. This is in fact the same number of unsafe acts committed for every fatality portrayed in the accident triangle.

At work we are regularly encouraged to report near misses and unsafe acts so that we can prevent death’s and serious accidents from happening, but each one can contain anything from a heavy object nearly hitting someone to a papercut. All this takes time, leads to a mountain of paperwork which gets unattended, not solved or corrected, results in worker dissatisfaction and in some cases makes a mockery of the safety team.

Also, when trying to be proactive and put a positive spin on safety we collate the information into so called lag and lead indicators which appear to give the impression that things are becoming safer, but in reality all they are doing is recording the quantity of things reported rather than indicating how things can be improved. Anything that is measures becomes in itself a lagging indicator because it occurred in the past, so the number of near misses reported, the number of safety meetings conducted, the number of corrective actions closed out are merely numbers with no actual meaning.

The Way Forward – Incremental Innovation

If we really want to make real big dent in workplace incidents, it’s perhaps time to change from our conventional methods to more divergent systems, utilizing new technology to process and record information, which will allow people to pursue their highest goals and aspirations and make the world a truly safer place?

Social media has become a big part of our lives, so we need to enhance this and start using Facebook to report positive actions and ask for the most likes?

Perhaps we need to immerse ourselves in 3D virtual reality systems so that we can visualise what it would look like to be in a car accident and see our families looking on at our dead bodies. Instead of undertaking a safety briefing at the start of the day, how about giving Go Pro cameras to workers to record their safety performance and allow the time at the end of the shift to analyse their performance?

Often the most effective way to improve is the simplest. So instead of using complicated systems with information that our brains can’t understand and hardly remember, we should be simply assessing what we do throughout the day and asking ourselves what we can do better?

By Mark Taylor – Director – Safety Matters (NZ) Ltd

Bibliography

Books

Rainy Brain, Sunny Brain: The New Science of Optimism – Elaine Fox

Risk Savvy – Gerd Gigerenzer

Rewire Your Brain – john b Arden

Sort Your Brain Out – Jack Lewis & Adrian Webster

Your Brain at Work – David Rock

Seeing What Others Don’t – Gary Klein

Flow – Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

Research

Brain study reveals how long-term memories are erased – http://www.jneurosci.org/content/36/12/3481

Less reward, more aversion when learning tricky tasks – https://news.brown.edu/articles/2014/11/conflict

Our brain activity could be nudged to make healthier choices – http://news.berkeley.edu/2016/06/08/healthier-choices/

Our futures look bright, because we reject the possibility that bad things will happen – http://www.psychologicalscience.org/index.php/news/releases/our-futures-look-bright-because-we-reject-the-possibility-that-bad-things-will-happen.html

New study delves into what makes a great leader – http://www.utsa.edu/today/2016/02/creativeleaders.html

Brain Activity Differs for Creative and Non-Creative Thinkers – http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2007/10/071027102409.htm

Brain On Autopilot: How the Architecture of the Brain Shapes Its Functioning -http://www.mpg.de/7738341/brain-architecture-daydreaming

Brain Stimulation Affects Compliance with Social Norms – http://www.mediadesk.uzh.ch/articles/2013/hirnstimulation-beeinflusst-einhaltung-von-normen_en.html

Brainstorming ‘Rules’ Can Lead to Real-World Success in Business Settings – http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2010/09/100927105205.htm

Complex Decision? Don’t Think About It – http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2008/12/081209154941.htm

Drivers’ hand positions on the steering wheel while using Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) and driving without the system – http://www.hfes-europe.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Piccinini.pdf

The effects of drivers’ speed on the frequency of road accidents – http://www.20splentyforus.co.uk/UsefulReports/TRLREports/trl421SpeedAccidents.pdf

Relationships Between Boredom Proneness, Mindfulness, Anxiety, Depression, and Substance Use – file:///C:/Users/Mark/Downloads/159-214-1-SM.pdf

Cognition and Emotion – file:///C:/Users/Mark/Downloads/Schachter_and_Singer_-_Cognition_and_Emotion%20(2).pdf

Do you have any thoughts? Please share them below