Censorship and Taboos in Safety

One of the interesting things we do in SPoR workshops is an audit of language, just a simple psychoanalysis of words associated with a key word. For example, ask any group what they associate with the language of ‘safety’ and the responses are dominated by: controls, hazards, compliance, regulation, injury, fatality, SWMS, Risk Assessment, protection, Litigation, legal, training, PPE, Hierarchy of Control, duty, paperwork, rules, competence, ALARP and mitigation.

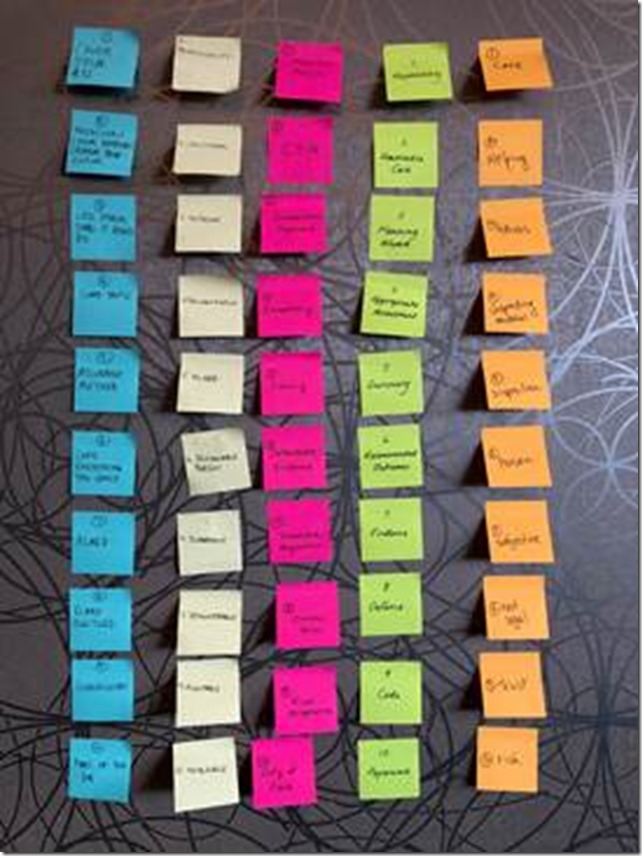

We usually start the activity with a brainstorm in groups, rank order by level of perceived importance and then transfer to sticky notes and place on a board see Figure 1. Recording and Sorting Process.

Figure 1. Recording Process.

We then look at the assembled language and see the collective discourse of the group. In a class of 20 people for example we would have 5 groups of 4 so 50 words listed on the board together see Figure 2. Language Discourse.

Figure 2. Language Discourse

What is fascinating about this activity is not the words present but what is absent from the list. Critical words such as: care, helping, trust, learning, listening, understanding, ethics, empathy, imagination, creativity and unconscious rarely make the list. If any of these words do make the list they usually amount to less than 5% of the total words listed.

What this audit demonstrates is a range of invisible social taboos that shape the language of the safety industry. This self-imposed silence on critical words for humanizing and professionalizing the industry acts as a form of social censorship. The higher up the career chain one goes the more one is likely to see the word zero. If ever this is done with people on the tools at the face where the real risk is, zero never appears. I have undertaken this activity with more than 25,000 people over the last 10 years. No-one who faces the most serious risks associates the language of ‘zero’ with safety.

It’s also fascinating how the safety industry cultivates ‘hard’ talk about risk and relegates people skills to ‘soft’ skills. The reverse is the case, it is a piece of cake to be mean and brutal to someone by demonizing their name or race but much harder to express care, help and tolerance for someone who doesn’t seem to understand the world as you.

The reason why social censorship prevails in this way in the safety industry is because the industry is the closed domain of a few disciplines. Just observe what happens when something goes wrong or an enquiry is required: first cab off the rank is a regulator, scientist or engineer, a sure recipe for keeping social censorship in place. The Brady Report and Boland Review are classic examples of ensuring everything stays the same, paperwork increases and the solution to safety is more systems.

We all censor language and we know we are doing it. When young children are about we all know what language doesn’t make it to airspace. People know know how to control their language consciously and this often leads to being able to maintain a certain discourse unconsciously. Similarly, those who hear their own children saying obscenities back to them learn quite quickly just how much their unconscious language takes effect.

In social contexts we all know what language is taboo and what is not. We learn this quickly in a group when we speak language deemed inappropriate. We all know what to say and NOT to say. This is why legislated warnings against gambling are stuck in the corner of a poker machine in gold on gold plaques in font 6. If you wandered around a casino talking about the harm of gambling, you would be soon ushered out the door. Casinos are places where we talk about winning, not misery, addiction and harm

When we examine cultural conventions for politeness and impoliteness we observe orthophemism (straight talking), euphemism (sweet talking) and dysphemism (speaking offensively). When my steel fixer mates are about it’s quite normal to ‘swear like a trooper’ and pretty soon you will be told to ‘drink a cup of concrete and harden the f*#k up princess’ if you start crusading about safety. I find it so entertaining when I hear regulators and managers run a campaign about ‘speaking up’ when they run a fear campaign on zero for the other 50 weeks of the year driving distrust, hiding and suppression.

When we are more savvy about what we are saying (https://safetyrisk.net/what-are-you-trying-to-say/ ) it is rarely the direct language that hits the unconscious. If the spoken word is incongruent with actions, symbols, artefacts or discourse then what message sinks in has nothing to do with the overt message that managers seem to think work. Most taboo is not learned overtly but covertly. Safety should have learned a long time ago that the medium is the message (https://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/mcluhan.mediummessage.pdf).

The constructive way forward can’t come from the same old sources. You can’t get vision from consulting the same old source. You can’t seek improvement in safety discourse from regulation, science and engineering. None of these disciplines have any focus at all on the nature of language, discourse, socialitie and political ethics. This is not about throwing out the baby with the bathwater but rather expanding the horizons of an industry bogged down with little vision beyond more of the same.

No amount of measurement, IT systems or data is going to shift a culture bogged down in the language as evidenced at the start of this blog. We’re not going to humanize safety with nonsense language like Resilience Engineering, The discourse has to shift away from systems, numbers, metrics and objects, and this will only come when safety makes the move to a transdisciplinary notion of learning (https://safetyrisk.net/transdisciplinary-safety/; https://safetyrisk.net/the-value-of-transdisciplinary-inquiry-in-a-crisis/ ; https://safetyrisk.net/transdisciplinary-thinking-in-risk-and-safety/ ).

Do you have any thoughts? Please share them below