Originally posted on October 23, 2015 @ 8:28 AM

The Convenience of Complacency

One of the cultural characteristics of the safety industry is fundamental attribution error . It seems that safety seeks blame before it breathes, you certainly need to if your job title includes zero.

One of the cultural characteristics of the safety industry is fundamental attribution error . It seems that safety seeks blame before it breathes, you certainly need to if your job title includes zero.

Whenever there is an event in comes safety to quickly ensure that everyone in the ‘wrong’ is deemed ‘negligent’ or ‘complacent’. Linkedin is littered with safety people posting silly pictures of people doing ‘dumb’ things (many photoshopped) to demonstrate how safety is superior and others are ‘negligent’ or ‘complacent’. The assumption and belief is that people wander around worksites just waiting to suicide or hurt others and that things are kept safe only when the safety guy (‘Hazardman’) is on hand. This is because others are stupid. The Danny Cheney story that circulated on the Internet for a few years is a classic example of this belief.

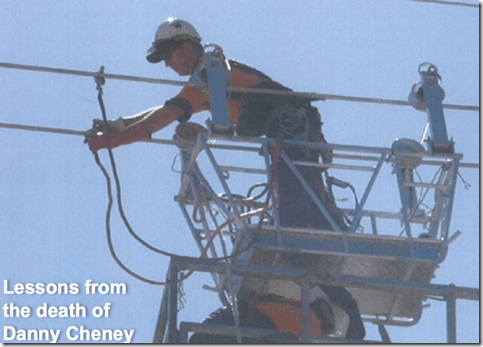

EXTRACT FROM THE LESSONS REPORT (See Full Report: Danny Cheney Fatality Learnings )

On Saturday December 5th Danny Cheney, employed by John Holland as a construction manager, died as a result of receiving electric shocks from induced current while working on the Strathmore to Ross high voltage transmission line near Townsville, Queensland. His colleague, Manquin Parungao, also employed by John Holland as a EWP operator also received minor burns from electric shocks and was hospitalised for 36 hours. The work involved traversing a pair of conductors in a trolley to be suspended from the conductors to act as a mobile work platform to allow the installation of spacers between the conductors. The transmission line and the conductors were under construction and not energised at the time. The primary cause of the incident was the failure to properly earth the conductors before commencing work on the line. This was a tragic, senseless and needless death as the incident was totally preventable.

The photograph that you see here was taken just seconds before Danny Cheney received the fatal shocks

The purpose of this briefing today is to understand from the incident investigation findings what was the work involved, what went wrong, why it went wrong and how it could have been prevented – and to ask ourselves what would we need to do to prevent such a death of someone on our team

Both these words ‘negligent’ and ‘complacent’ may have legal definition but it is their psychological attribution is rarely discussed. The word ‘negligent’ essentially means ‘not picking up on something’. It is interpreted as a failure to exercise care, not an act of intentional harm. However, there are hundreds of social-psychological reasons why humans don’t ‘pick up on things’ that have nothing to do with carelessness. For example: the fact that humans develop heuristics to ensure rapid decision making leads to mistakes that have nothing to do with carelessness or negligence. This is discussed in HB 327:2010 Communicating and Consulting About Risk, the handbook to the Risk Management Standard AS/NZS ISO 31000:2009. Let’s read a bit from the handbook (p.13).

‘Heuristics are valid risk assessment tools in some circumstances and can lead to “good” estimates of statistical risk in situations where risks are well known. In other cases, where little is actually known about a risk, large and persistent biases may give rise to fears that have no provable foundation; conversely, such as for risk associated with foodborne diseases, inadequate attention may be given to issues that should be of genuine concern.

Although limitations and biases can be easily demonstrated, it is not valid to label heuristics as “irrational” since in most everyday situations, rule-of-thumb judgments provide an effective and efficient approach for estimating risk levels. It’s not unusual for specialists to also rely on heuristics when they have to apply judgment or rely on intuition.

But heuristics often leads to overconfidence. Both lay people and specialists place considerable (sometimes unjustified) faith in judgments reached by using heuristics. In particular, “awareness” of a hazard does not imply any other knowledge than that the hazard exists, but people may be tempted to pass judgment and make decisions based on this alone.’

So, the very rules-of-thumb that we all create in order to live and work quickly ‘without thinking’, are in themselves positive and can also have implications for how humans ‘don’t pick up on things’. The habits we develop so that we can work quickly and develop ‘flow’ (see Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi) are also problematic under any turbulence, misdirection and change. Many times humans don’t pick up on things not because they are careless, but because organisations encourage workers to efficiency and work ‘without thinking’. Sometimes this looks like overconfidence and sometimes safety is quick to label this as ‘complacency’ or ‘negligence’.

Another psychological phenomena that applies to the idea of negligence is desensitization. The nature of humans is to become desensitized to things that are repeated and given regular exposure. The classic examples of this is how we accept the risks of driving on the road or how the thrill of romance diminishes over time. It is so easy to attribute carelessness and complacency to desensitization. The moment we find our label (complacency) everything is somehow explained, end of enquiry. We don’t really know why we were ‘not thinking’ or why someone else was ‘not thinking’ or why we have lost sensitivity to feelings but the deficit label helps us close the case and attribute meaning. When we fumble things, have accidents, spill our coffee, bump into someone at the shops, drop the lid off the bottle, lose that romantic edge or trip on our own foot, that’s just oops!

There are a host of factors that affect our perceptions of fault or cause that most incident methodologies completely disregard. Let’s read from HB 327:2010 again:

‘Although technical specialists may have access to additional “objective” measures from their own disciplines, they too will also use their own subjective perceptions of a situation. For everyone, perceptions are proven to be influenced by—

· whether the risk is voluntary or involuntary;

· how much control one can exercise over the risk;

· whether the risk is familiar or unfamiliar;

· whether the consequences are likely to be common or dreaded; immediate or delayed;

· the severity of the consequences;

· who benefits;

· the degree of personal exposure to harm or loss;

· the perceived necessity of exposure;

· the size of the group exposed;

· the effect on future generations;

· the global catastrophic nature of the risk;

· the changing character of the risk;

· whether the hazard is encountered as part of one’s occupation; and

· whether the consequences are reversible.

In addition to these factors a number of demographic and socio-economic determinants such as age, sex, education, social class, ethnicity and income strata also affect individual and group perceptions.’

This is why the Human Dymensions SEEK Event Investigation Program explores these factors (and more) before pursuing any training anyone in investigation methodology. There are over 250 different factors that can be added to the list above that affect perception and judgment about risk. In most investigations we conduct we find social-psychological causes of decision making rather than global (unspecified) causes such as negligence or complacency. Neither of these words tell us much about the real nature of decision making.

Complacency is defined as ‘a feeling of contentment or self-satisfaction, especially when coupled with an unawareness of danger, trouble, or controversy’. But this too is attributed and could just as easily be automaticity or overconfidence. The act of undertaking tasks in automaticity naturally cultivates overconfidence. We repeat tasks, gather speed, habituate performance, develop heuristics, desensitize ourselves to risk, automate thinking and process, become blind to turbulence and cues, institutionalize workflow and enculturate associated values. Then when something goes wrong it’s simply complacency or negligence.

The trouble in safety is that deficit values are attributed to complacency including ideas such as: smugness, carelessness, intentionality and neglect. There you go, I know why he didn’t isolate the hazard, ‘he’s an idiot’. Brilliant event investigation, case closed.

We also observe on Linkedin safety the constant quest to keep things simple, if anyone understands safety as complex this is deemed a construction and an inadequacy of the individual to follow the KISS principle. When we follow the KISS principle we end up with safety nonsense such as ‘all accidents are preventable’ and ‘people chose to be unsafe’. There seems so much contentment in safety when it finds out someone was complacent or negligent or careless as if these actually explain decision making. The denial of complexity keeps simple safety in the simplistic space, content with complacency but still not knowing cause because it doesn’t know what to ask. It’s much easier to find a generalistic cause that actually explains nothing.

When we learn not to rush in with labels and blame, when we are slow to gravitate to complacency and neglect and understand the social-psychology of risk, we actually find far more sophisticated understanding as to why people do what they do. Then with such understanding we can move from guesswork to developing new ways to better manage risk at work.

William McGinty says

What an interesting article, I and some of my associates believe that Safety is far more complex then just getting to zero. Maybe if more people looked at the complexities behind why an organisation’s safety is terrible/bad or just normal. Unfortunately getting people even one’s own peers to look out side just safety and give some understanding to the difference forces that effect a safe outcome then I think that we will be able to move further forward then the end of out nose

Robert Long says

William, its such a part of the culture of safety to just accept what is, police checklists and don’t question anything. I’ve been in this space for 20 years and nothing has changed. The curriculum is the same, the associations are the same and culture the same. Same old binary simplistic stuff and very few motivated to step outside the safety box.

How strange that the industry actually thinks that complacency has meaning? It gives no explanation of why people do what they do. Of course, if you believe ‘safety is a choice you make’ then obviously people chose to be complacent. None of this is true or real, the complexities of human being are completely ignored by this behaviourist industry that would rather have its head in the sand than learn.